The MoD’s lead on Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) acknowledged that repeated exposure to blasts generated by some army weapons can injure the brain, as ITV News Science Correspondent Martin Stew reports

Words by ITV News Assistant Producer Robbie Boyd

Thousands of serving troops may be suffering from brain damage after being exposed to harmful blast waves from the British Army’s weaponry, an ITV News investigation has revealed.

In a landmark admission, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) confirmed that weapons systems used by the army are causing brain damage in soldiers.

Speaking to ITV News Science Correspondent Martin Stew, the MoD’s lead on Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), acknowledged that repeated exposure to blasts generated by some army weapons can injure the brain and lead to life‑long health conditions.

Lt Col James Mitchell said during earlier campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, the perception was that large munitions and impact blasts were the primary cause of TBI and concussion among British soldiers.

However, that is no longer the case, with TBI and concussion being blamed on the impact on soldiers from their own weapons systems.

“Over especially the last five to ten years, we’re starting to appreciate the role of what we call low level blasts,” he explained.

He said these low level blasts were predominantly being caused by “the exposure of our service personnel to blast over-pressure from their own weapons systems”.

Lt Col Mitchell added that while exact figures are not known, “thousands” of serving personnel have been exposed to harmful blasts, with figures potentially even higher for veterans affected.

Lt Col James Mitchell, the MoD’s lead on Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), acknowledged thousands of troops may be suffering from brain damage after being exposed to harmful blasts

Most at risk are those who have been repeatedly exposed to heavy weapons, including mortars, some shoulder-launched anti-tank weapons, 50-calibre rifles and machine guns, or explosive charges.

Explosions create a wave of ‘overpressure’, a spike in the surrounding air pressure above normal atmospheric levels caused by a blast wave.

It can create a force so strong that it penetrates the skull, and the energy transferred to the brain causes microscopic damage to blood vessels and neurons.

Repeated exposure can overwhelm the brain’s ability to heal itself, causing serious long-term neurological damage.

Symptoms of blast-related TBI overlap with those of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), making it difficult to diagnose.

They may include: severe headaches, visual disturbances, sensitivity to noise and light, memory loss and a sense of personality change.

Now, scientists around the UK are hoping to explore the potential causes of TBI, with financial support from the MoD.

The University of Birmingham is playing a key role in the mild TBI study in partnership with the MoD, which aims to estimate what kind of brain damage veterans have.

Professor Lisa Hill is a neuroscientist at the University of Birmingham.

She explained that when the brain is damaged, it releases biomarkers, biological clues that can help scientists understand what and where the damage is happening.

“If somebody gets injured, it changes the structure and function of the brain, but it also releases chemicals that you wouldn’t normally see,” she said.

“So if we can measure things in blood or in their saliva, that can tell us how potentially bad their injury has been and what symptoms they might go on to get.”

But policy changes might need to be made in order to reduce or prevent injuries in the first place.

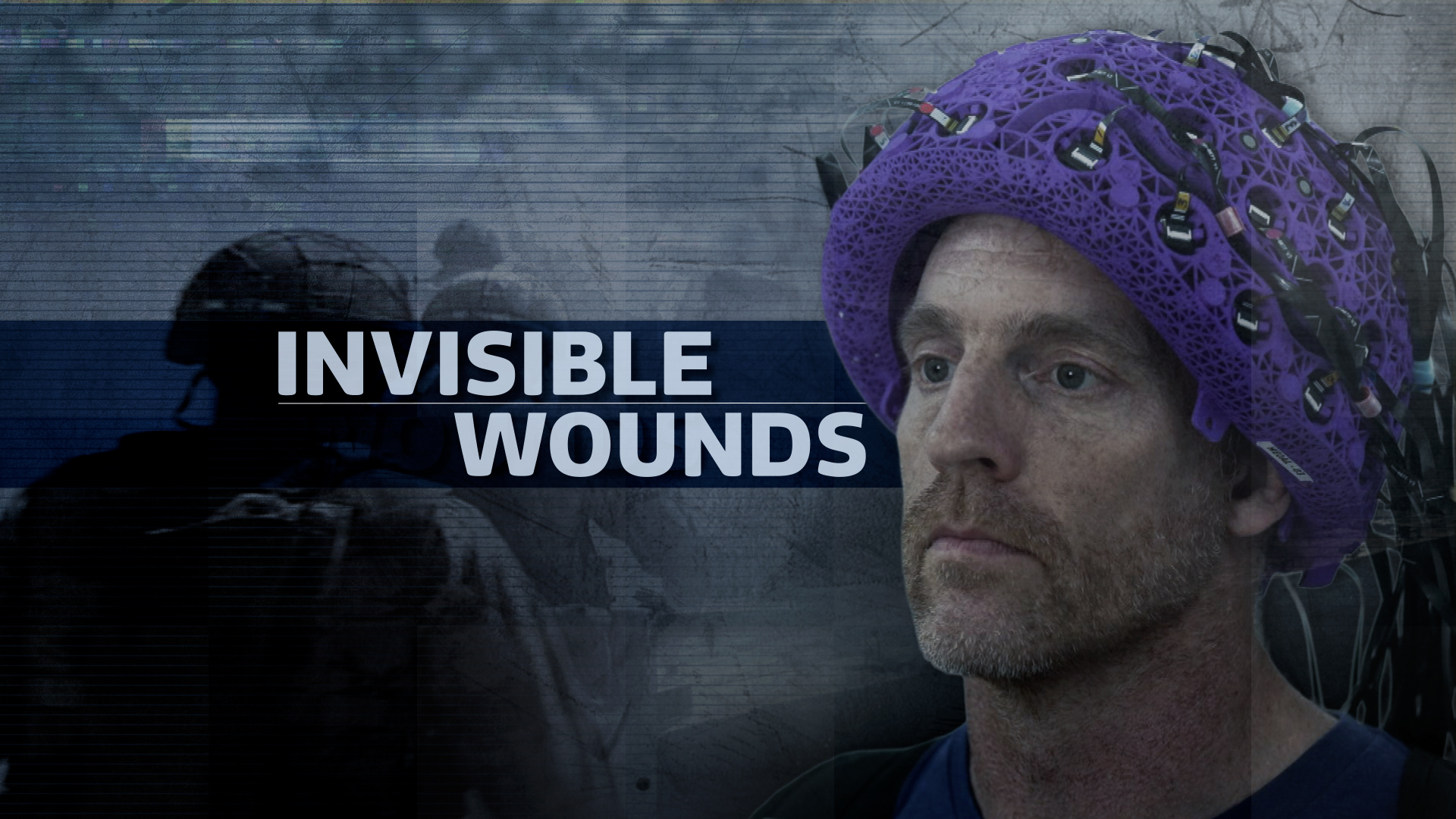

Professor Karen Mullinger, an expert in neuro-imaging at Nottingham University, is working to identify patterns of damage with sophisticated brain scanning technology called OPM MEG.

Hugh Keir, a sniper with the Parachute Regiment who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan, now runs the H-Hour podcast which is popular with veterans in the UK and abroad.

He volunteered to undergo a trial scan to see if his years of exposure to blast have left a mark.

The results showed normal brain activity overall, but there were some signs that may indicate damage.

To be certain, Prof Mullinger and her team need to scan many more veterans and controls to build up a database of what “normal” looks like.

In time, it is hoped there will be enough data to allow for definitive diagnoses.

Professor Mullinger also plans to study soldiers in real time, to see which activities are highest risk.

“We can scan these soldiers before they go and do a training exercise and then immediately after, then we get a baseline which is specific to them,” she said.

“If the ’wire paths’ have been damaged by blasts or whatever else it might be, then the function is going to change.”

The information collected from these trials could shape policy, such as modifying the most damaging weapons or reducing blast exposure in training exercises.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues raised in this article, help is available

- The charity Samaritans operates a 24/7 helpline (116 123) for anyone who needs somebody to talk to. Further resources can also be found on its website.

- Concussion Legacy Foundation supports British current and former serving members and their families

- The Concussion Legacy Foundation also provides a personalised helpline for those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country