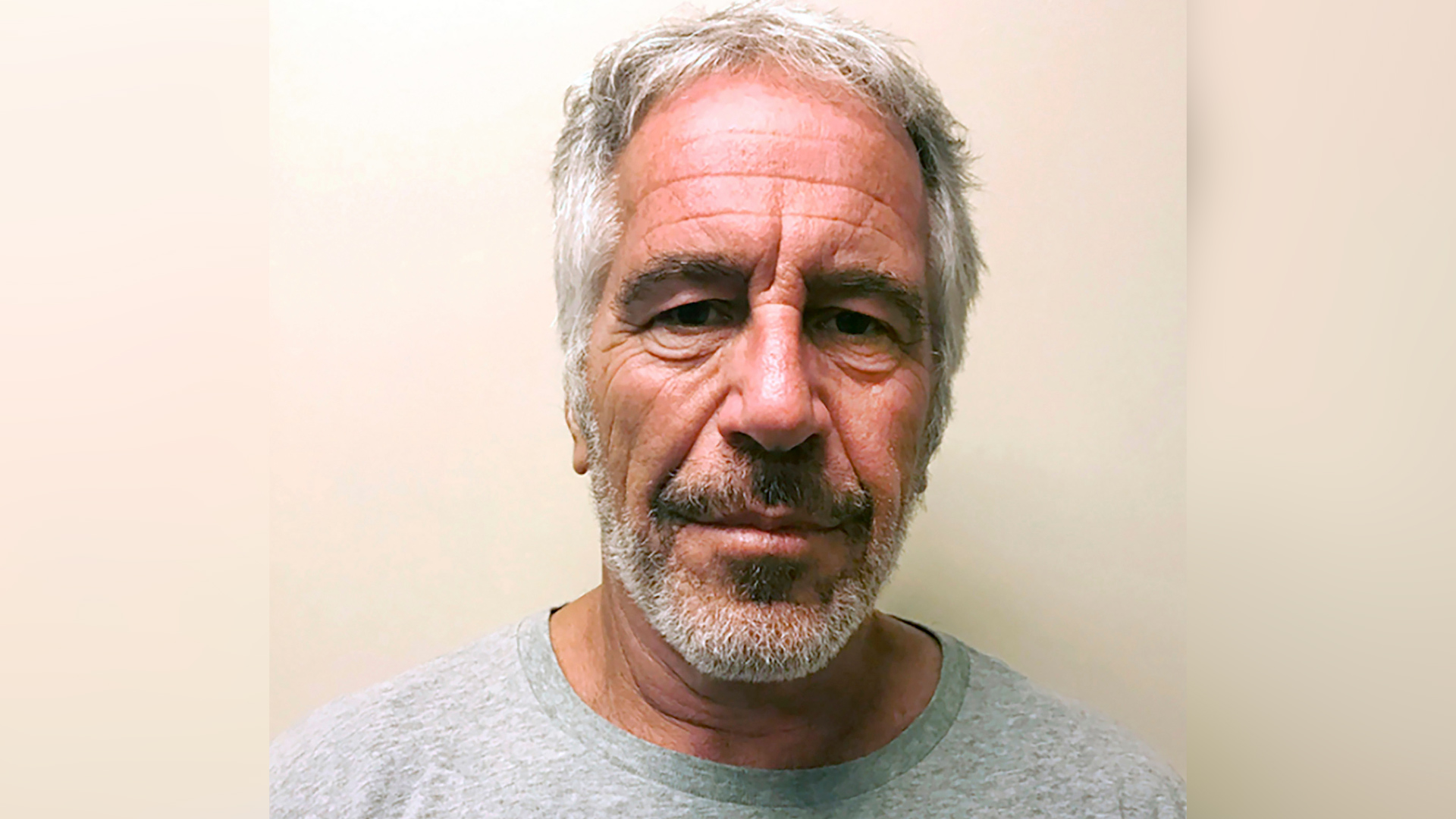

ITV News Deputy Political Editor Anushka Asthana and Labour Deputy Leader Angela Rayner sat down in April to discuss how Bipolar disorder has shaped their lives

“It’s just nothing. It’s just pain…

“She can’t move… She doesn’t want to live.

“It’s just real, deep, deep sorrow.”

I was sitting opposite Labour’s deputy leader, Angela Rayner, in the middle of an interview quite different to those I would normally be expected to carry out.

We were not sparring over workers’ rights or questions of tax and property. Instead, in this conversation for ITV News, she was describing the sheer depths of depression suffered by her mum.

In between painful anecdotes, including the anger she sometimes felt as a child, Rayner kept reminding me how proud she was of Lynn Bowen. “Even in her darkest hours, she tried her best,” she said.

Bowen suffered with Bipolar disorder, and ever since I heard Rayner talk about it, on the Leading podcast with Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart, I’d been desperate to discuss it with her myself. There was one thing she said that made me stop in my tracks.

If her mum had received support earlier, Rayner thought it may have transformed her life.

The comment immediately turned my mind to my brother – who also suffered with Bipolar disorder but sadly died at the age of just 37. Had he been diagnosed much earlier – would things have been different for him too?

My experience of watching a loved one ride the rollercoaster highs and lows of this illness was not always bad, by any means.

My brother was highly intelligent and one of the most brilliantly creative people I’d ever known. He won a place at Cambridge University, as well as being a wonderful musician, talented artist and the type of friend from whom love just poured out.

But his mental illness also brought huge pain and confusion, leaving him and us feeling – at times – utterly helpless.

Through him I met others with Bipolar Disorder too, who would try to describe the sheer disconnection of the psychosis they experienced – arguing that their highs could trigger behaviour just as life-threatening as their suicidal lows.

At one point, I witnessed the sharp end of mental health services, immediately followed by the most critical side of physical health provision – and I was shocked by what I saw. The gulf between the two when dealing with similarly serious conditions felt extreme.

In one case it took a week to see a consultant – in the other, we received that level of care within just minutes.

When I wrote a letter of complaint to the mental health unit after my brother died, they called me in for a meeting.

I walked nervously to the end of a plain, clinical corridor and sat opposite them, behind a desk.

I told them I was shocked by the lack of provision. To my surprise, they agreed and pointed to my job (back then chief political correspondent at the Times).

“You are a journalist; can’t you write about it?”

In truth, I’ve not felt able to talk about my brother until now, but something in Rayner’s interview made me change my mind. Maybe my experience could help me highlight some of these issues.

Have you heard our new podcast Talking Politics? Every week Tom, Robert and Anushka dig into the biggest issues dominating the political agenda…

In the decade since that happened, there has been a lot of talk about parity of esteem between physical and mental health, but I still see many of the same challenges. Bipolar UK tell me that over a million people live with this illness in Britain, and yet it still takes, on average, 9.5 years to get a diagnosis.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists call that delay “unacceptable”. They warn of a “lost decade” in which people can lose jobs, relationships, homes and even lives.

For some that is down to suicide – for others – like in our case – it is more complicated.

Now, the College is calling for that decade-long delay to be urgently cut in half.

My brother had the wonderful support of medical parents who knew how to get him to the right care, but even in the most acute settings, that Bipolar diagnosis and therefore the most appropriate treatment was delayed.

In the end, he died of a physical, lung-related disease, but we don’t believe he would have fallen ill if it weren’t for the risks he took as a result of his Bipolar.

As a child, Rayner told me she did not have the words to describe what was happening. “For me, it wasn’t a title or condition. It was more, why is my mum different? My friends, their mums were able to have their clothes ready in the morning for them for school, they would make their breakfast.”

She described asking friends if she could go round for tea, and if their parents said no (because it was the second day in a row) she would sit on the curb and wait. “I always remember feeling hungry as a child,” she said.

Bowen also struggled to read and write, resulting in her once bringing home a can of dog food that she thought was stewing steak – and, another time, shaving foam instead of cream.

I ask about any regrets she might have – as I know I have plenty, and then turn to that delay in diagnosis, wondering – would my brother be here if he’d had that information ten years earlier?

“My mum spent weeks in hospital when she didn’t need to be in hospital. If she had got the intervention early on, and the support early on, she would not have ended up in that crisis point,” admitted Rayner.

Sameer Jauhar – one of the country’s leading experts on Bipolar disorder, said one of the big problems is that the delay in diagnosis can stretch from the late teens to the early thirties – a critical time in which people are developing relationships and life.

“The rates of self-harm, suicide are tremendously increased,” he said – adding that the treatment for Bipolar depression differs from other forms.

One mistake can be giving a person with Bipolar – antidepressants that can actually drive their mania.

But with an early diagnosis, he said there were now effective treatments and interventions.

That is why he is suggesting much earlier screening for Bipolar and even the use of AI to scour medical records to look for clues.

How one quick diagnosis changed one man’s life

Sam Swidzinski was a teenager when he started to realise that something was not right.

Bouts of depression were punctuated with strange highs. “I wanted to be the fastest person to run around the whole world,” he said – gesticulating in a circle.

“I was starting to come up with plans for how I would run over the water.”

This revved up energy was a sign of hypomania, though he did not know it at the time. What he did know: was that more and more friends seemed to be drawing away from him.

Then came full-blown psychosis. “That was really rough. I was hallucinating, seeing things that weren’t there, also hearing things that weren’t there. I had strange, very peculiar delusions.”

Sam was struggling to hold down work by then, so to raise some extra money he volunteered for a research project which involved Sameer Jauhar – a psychiatrist at Kings College London.

Sameer carried out a brain scan on Sam. Pairing that with a detailed history of his symptoms, he thought he knew what might be going on.

Soon Sam had a diagnosis for Bipolar disorder four and a half years after his symptoms started – much shorter than the average 9.5.

What did that early diagnosis mean for Sam? “I don’t think I’d be alive today,” he answered immediately.

“There’s many different ways I could have died,” he said – arguing that he felt suicidal at times, but also behaved recklessly when psychotic – once being hospitalised after trying to down a liter of rum when challenged.

“I had no concept… that could lead to a negative consequence.”

Instead, sitting opposite Sameer in the KCL canteen, Sam credits the leading psychiatrist with saving his life.

With treatment, he was able to study psychology and is now working with Sameer as he completes a PhD on Bipolar.

Sam said those interventions put him back on track. And relationships?

“I’m married now, so that’s a big one!” he said, grinning widely, and flashing up his wedding ring.

If you have found the topics discussed in this article distressing, you can seek help and advice at the following places:

- Samaritans operates a 24-hour service available every day of the year, by calling 116 123. If you prefer to write down how you’re feeling, or if you’re worried about being overheard on the phone, you can email Samaritans at jo@samaritans.org;

- You can call the NHS on 111;

- You can text “SHOUT” to 85258 if you would rather not speak to someone over the phone.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country