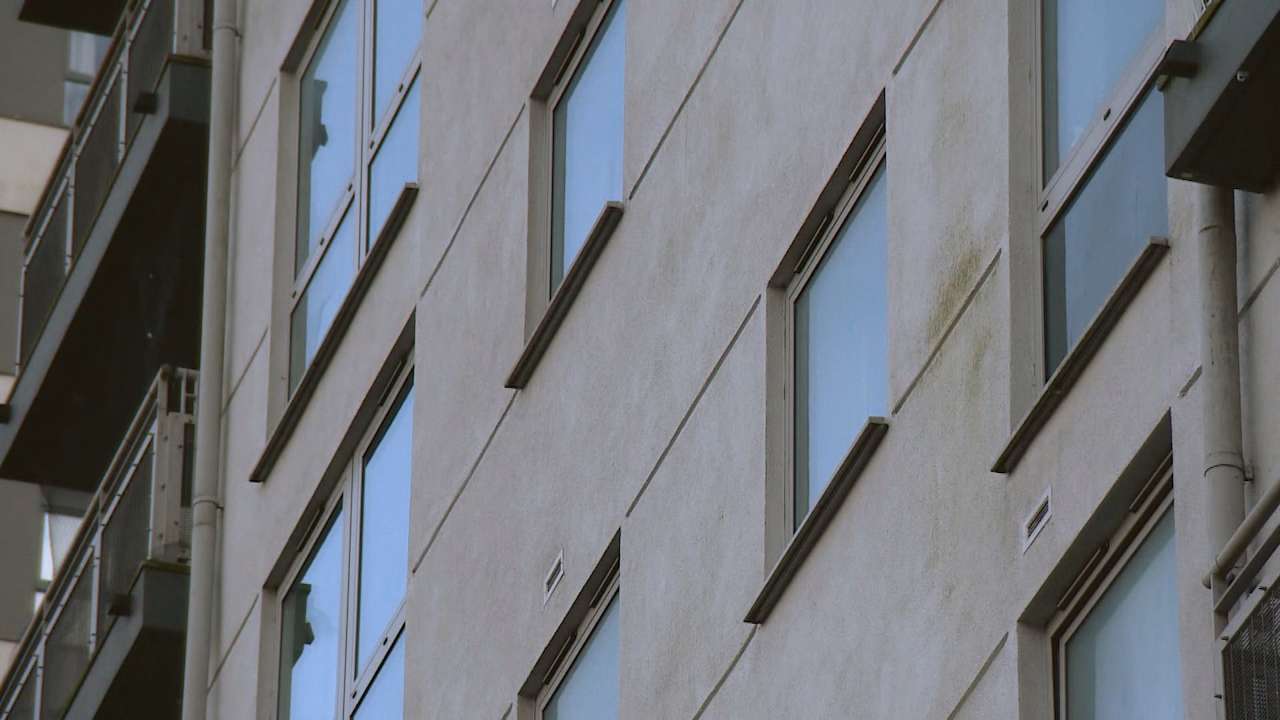

On June 14, 2017 the Grenfell Tower disaster claimed 72 lives.

Seven years later, the final report into the decades leading up to the blaze at the high-rise is due to be published on Wednesday.

The report into phase one, published in October 2019, concluded the tower’s cladding did not comply with building regulations and was the “principal” reason for the rapid and “profoundly shocking” spread of the blaze.

The long-running inquiry’s second report goes much further into question how the tower came to be in a condition which allowed the flames to spread so quickly.

It is not known what the report will conclude or who it will blame, the lead counsel, Richard Millett KC, described how a “merry−go−round of buck−passing” had prevailed throughout the hearings that made up the investigation.

Here, ITV News looks at what we can expect from the report.

What did we learn from the first report and what does it hint at for the second?

Inquiry chairman Sir Martin Moore-Bick said expert evidence had observed the fire was “unusual in the way that it spread laterally and was able to envelop the entire building in under three hours”.

In his first report, he said: “It is clear from what has been learnt so far that the building suffered a total failure of compartmentation. How the building came to be in that state is the most pressing question to be answered in phase two.”

Phase one concluded there had been a “total failure” of compartmentation – a term for the sub-division of a building by fire-resisting walls or floors to limit fire spread.

When moving onto the second phase of the inquiry Sir Martin said it would focus on the “decisions which led to the installation of a highly combustible cladding system on a high-rise residential building and the wider background against which they were taken.”

The first report also looked at the role of the London Fire Brigade (LFB) and said there was a general “failure properly to understand the risk of cladding fires in high-rise buildings.”

Who is being examined in the second report?

Along with the LFB, the government, Kensington and Chelsea council, the private companies that installed the cladding and the managers of the tower have faced scrutiny in phase two.

The material make-up of the cladding and the companies that produced and installed it are under the direct spotlight.

Kingspan

Kingspan produced an insulation product that was used in the cladding but has said it made up just 5% of the material used on the tower block. They have also said they were unaware their product was being used.

Former housing secretary Michael Gove has previously accused Kingspan of having done “nothing to contribute financially to the remediation costs required to fix unsafe buildings”.

Celotex

Celotex was the manufacturer of the majority of the insulation boards used in the refurbishment.

In a previous statement, the firm said during its investigations after the fire “certain issues emerged concerning the testing, certification and marketing of Celotex’s products” which involved “unacceptable conduct on the part of a number of employees”.

Rydon

Rydon was appointed in 2014 as the design and build contractor for the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower.

It has stressed it did not design or specify the cladding or insulation, and told the inquiry it had “engaged, in good faith” already-appointed architects to ensure the design complied with building regulations and engaged a specialist cladding subcontractor “to design and install compliant and safe material”.

Exova

Exova provided fire safety advice to Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO) for the proposed tower refurbishment.

A lawyer for the fire safety consultants told the inquiry the company was later “frozen out” of the project and Rydon, the firm that became the main contractor in 2014, had “consciously and deliberately” chosen not to appoint Exova as part of the design team.

Whirlpool Corporation

Whirlpool Corporation was the manufacturer of the fridge-freezer where, as confirmed in the first report, the fire started.

Inquiry chairman Sir Martin Moore-Bick said that while a fire starting in an electrical domestic appliance is not uncommon, “the important question” to consider is how that “could have had such catastrophic consequences for the whole building and its occupants”

The Royal Borough of Kensington Council

Sir Martin said also local authorities and the government would be part of the report, examining how the tower was managed, its fire safety provision and whether the regulations were up to scratch.

Prior to the second report being published the leader of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, Elizabeth Campbell, should have done more to keep our residents safe before the fire, and to care for them in the aftermath.

Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation

Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO) was criticised in the first report for having an emergency plan that was 15 years out of date.

In February 2018, less than a year after the fire, KCTMO handed back delivery of all day-to-day housing and related support services to the council.

Tower resident Edward Daffarn, who had previously raised safety concerns and predicted a “catastrophic event” at the tower seven months before the fire, told the inquiry the organisation had acted like “a mini-mafia” towards residents.

He said he had never believed the KCTMO was capable of keeping tenants safe, claiming staff at the organisation believed residents should be grateful to them and had labelled him a “troublemaker”.

The London Fire Brigade

The first report concluded that LFB#s performance “fell below the standards set by its own policies or national guidance”, with “justified concern” that the organisation had failed to learn from previous disasters such as the Lakanal House fire in 2009 in which six people were killed.

The phase one report said the stay-put policy was not questioned soon enough and recommended policies must be developed for managing a transition from “stay put” to “get out”, and that control-room staff should receive training on handling such a change of advice and conveying it effectively to callers.

The government

Finally, the government itself has been criticised for not recognising weaknesses in the regulatory framework for fire safety.

It insisted it is committed to “driving change” and referenced the Fire Safety Act 2021 and the Building Safety Act 2022, which it said “bring about lasting changes to overhaul a regulatory system that has been shown to have been unfit for purpose”.

There has been repeated criticism from bereaved and survivor groups at recommendations not being implemented by government – namely that the owners and managers of high-rise residential buildings be required by law to prepare personal emergency evacuation plans for residents unable to self-evacuate.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country