There was no word of additional protests against strict government anti-pandemic measures on Tuesday in Beijing, with police out in force and temperatures well below freezing.

Shanghai, Nanjing and other cities where online calls to gather had been issued were also reportedly quiet.

Rallies against China’s unusually strict anti-virus measures spread to several cities over the weekend in the biggest show of opposition to the ruling Communist Party in decades.

Authorities eased some regulations, apparently to try to quell public anger, but the government showed no sign of backing down on its larger coronavirus strategy, and analysts expect authorities to quickly silence the dissent.

PA Media

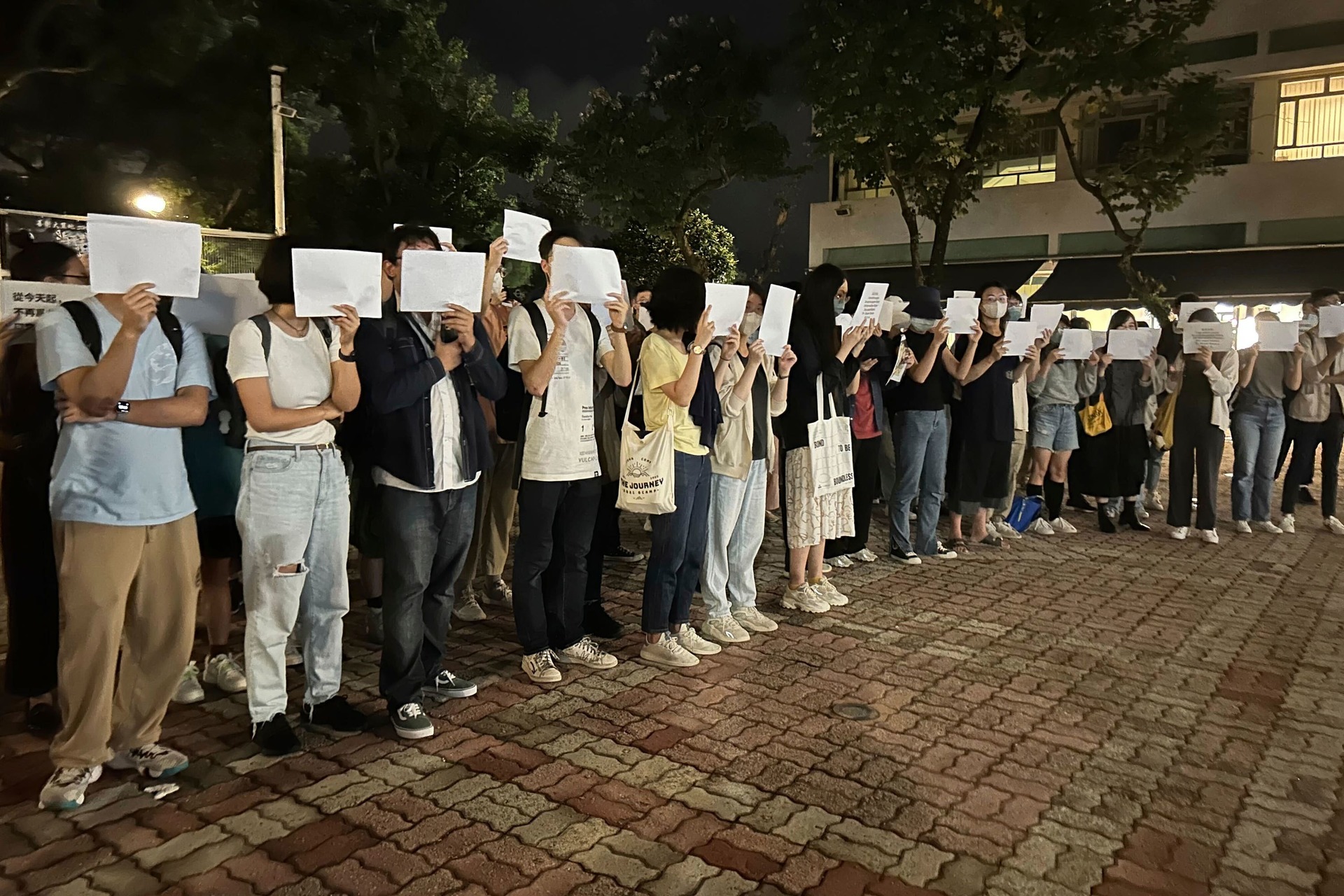

PA MediaIn Hong Kong on Monday, about 50 students from mainland China sang at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and some lit candles in a show of support for those in mainland cities who demonstrated against restrictions that have confined millions to their homes.

Hiding their faces to avoid official retaliation, the students chanted “No PCR tests but freedom!” and “Oppose dictatorship, don’t be slaves”.

The gathering and a similar one elsewhere in Hong Kong were the biggest protests there in more than a year under rules imposed to crush a pro-democracy movement in the territory, which is Chinese but has a separate legal system from the mainland.

PA Media

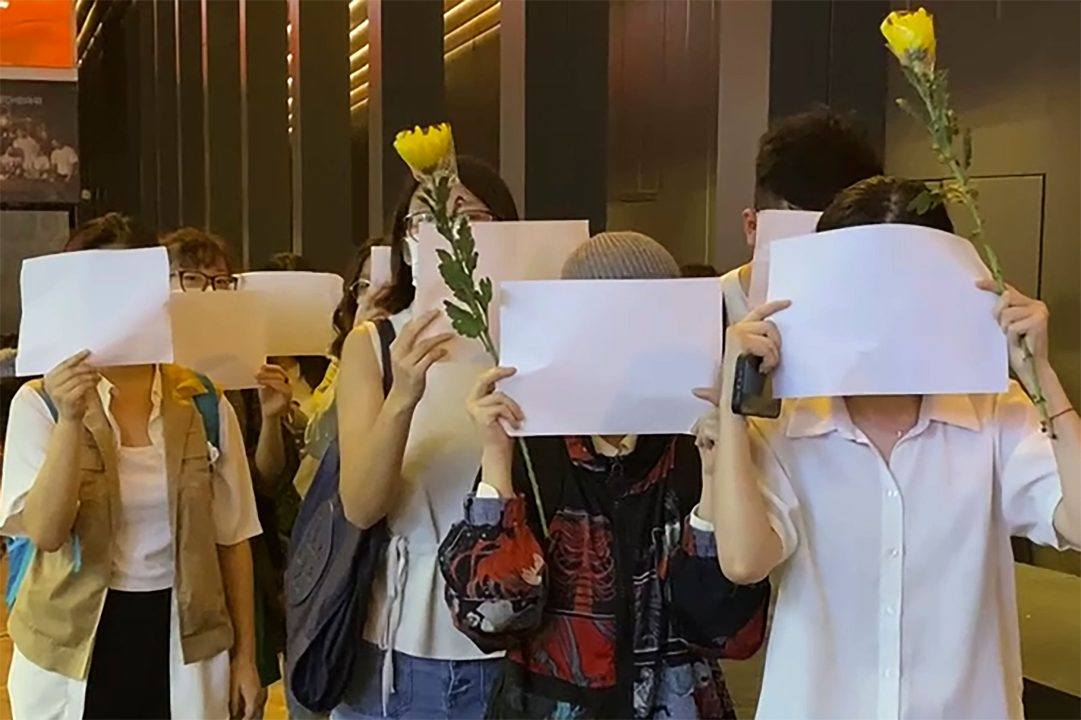

PA Media“I’ve wanted to speak up for a long time, but I did not get the chance to,” said James Cai, a 29-year-old from Shanghai who attended a Hong Kong protest and held up a piece of white paper, a symbol of defiance against the ruling party’s pervasive censorship. “If people in the mainland can’t tolerate it anymore, then I cannot as well.”

It was not clear how many people have been detained since the protests began in the mainland on Friday, sparked by anger over the deaths of ten people in a fire in the north-western city of Urumqi.

The incident prompted angry questions online about whether firefighters or victims trying to escape were blocked by locked doors or other anti-virus controls. Authorities denied that, but the fatal fire became a target for public frustration about the controls.

PA Media

PA MediaWithout mentioning the protests, the criticism of Xi Jinping or the fire, some local authorities eased restrictions on Monday.

The city government of Beijing announced it would no longer set up gates to block access to apartment compounds where infections are found.

“Passages must remain clear for medical transportation, emergency escapes and rescues,” said Wang Daguang, a city official in charge of epidemic control, according to the official China News Service.

Guangzhou, a manufacturing and trade centre that is the biggest hot spot in China’s latest wave of infections, announced some residents will no longer be required to undergo mass testing.

PA Media

PA MediaUrumqi, where the fire occurred, and another city in the Xinjiang region in the northwest announced markets and other businesses in areas deemed at low risk of infection would reopen this week and public bus service would resume.

“Zero Covid,” which aims to isolate every infected person, has helped to keep China’s case numbers lower than those of the United States and other major countries. But tolerance for the measures has flagged as people in some areas have been confined at home for up to four months and say they lack reliable access to food and medical supplies.

The ruling party promised last month to reduce disruption by changing quarantine and other rules known as the “20 Guidelines”. But a spike in infections has prompted cities to tighten controls.

On Tuesday, the number of daily cases dipped slightly to 38,421 after setting new records over recent days. Of those, 34,860 were among people who showed no symptoms.

The ruling party newspaper People’s Daily called for its anti-virus strategy to be carried out effectively, indicating Mr Xi’s government has no plans to change course.

Most protesters have complained about excessive restrictions, but some turned their anger at Mr Xi, China’s most powerful leader since at least the 1980s. In a video that was verified by The Associated Press, a crowd in Shanghai on Saturday chanted: “Xi Jinping! Step down! CCP! Step down!”

The BBC said one of its reporters was beaten, kicked, handcuffed and detained for several hours by Shanghai police but later released.

The UK broadcaster criticised what it said was Chinese authorities’ explanation that its reporter was detained to prevent him from contracting the coronavirus from the crowd. “We do not consider this a credible explanation,” it said in a statement.

Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Zhao Lijian said the BBC reporter failed to identify himself and “didn’t voluntarily present” his press credential.

“Foreign journalists need to consciously follow Chinese laws and regulations,” Mr Zhao said.

Swiss broadcaster RTS said its correspondent and a cameraman were detained while doing a live broadcast but released a few minutes later. An AP journalist was detained but later released.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country

PA Media

PA Media