Hunterston B has produced enough energy in its lifetime to power every home in Scotland for 31 years.

But at the stroke of midday on Friday, January 7, the North Ayrshire plant was shut down with the simple push of a button.

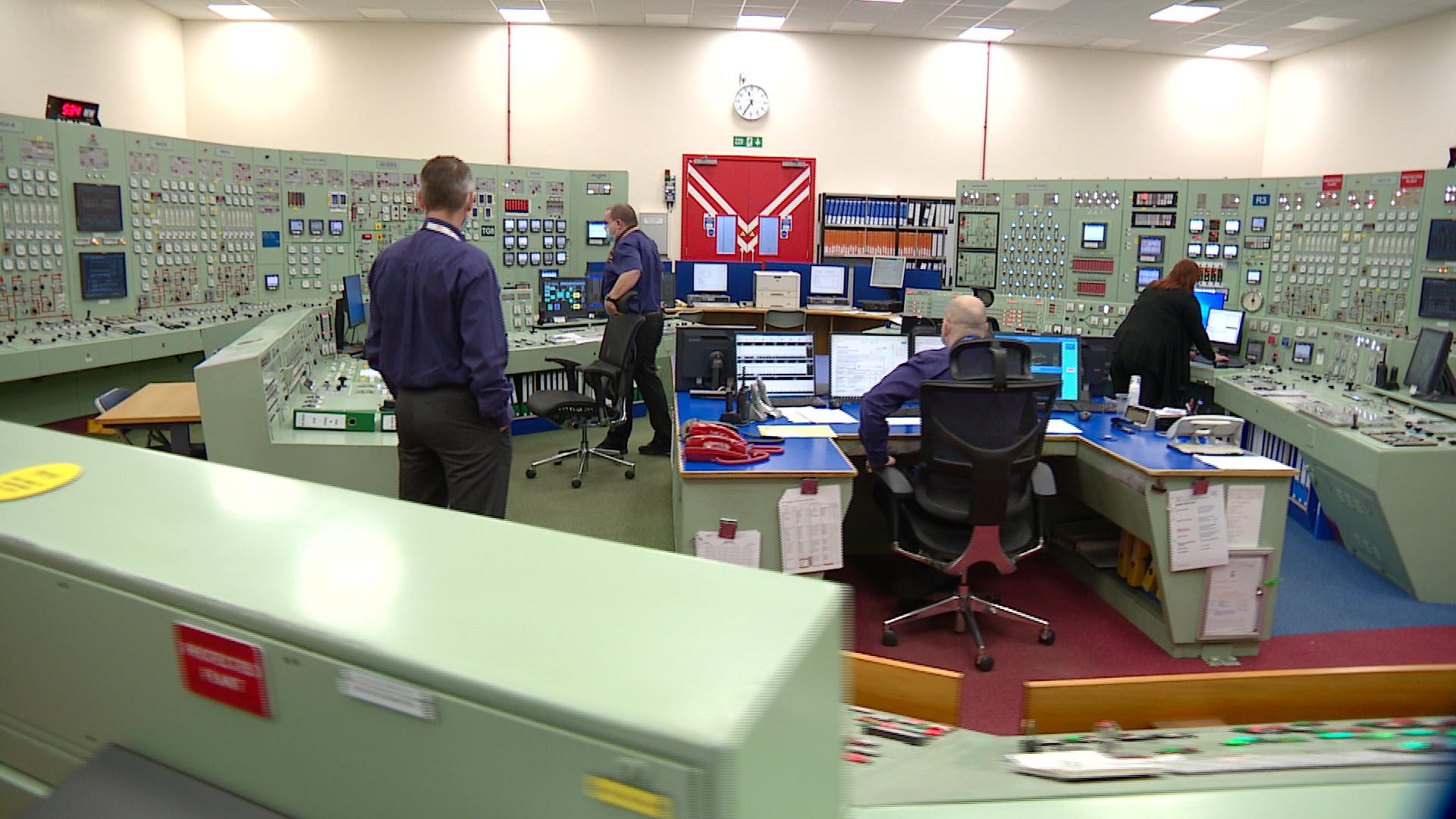

In the high-security control room, director Paul Forrest stepped forward and triggered the end for one of Scotland’s last nuclear power stations.

STV News

STV NewsIt took just a matter of seconds. Once the button was pressed, control rods containing boron drove into the core, catching neutrons and halting the nuclear chain reaction that has generated power for nearly half a century.

To the outside world, a billowing burst of steam into the sky was the most visible sign of change, as the intense heat of the cooling reactor is released as a dense mist, a final salute as the plant goes into shutdown.

STV News

STV News“The technology was designed back in the 60s, built in the 70s and we’ve been producing electricity here for 46 years,” said Mr Forrest.

“We’re using the same technology as 46 years ago, clearly the people have changed over that period, but many have dedicated their working lives to this station.

“Today’s our last day of generating electricity for Scotland, it’s a day of mixed emotions. There’s a degree of sadness, but I think a lot of staff are looking back with pride too.”

STV News

STV News‘Unchanged over the decades’

Inside the plant, much of Hunterston B is a visual reminder of the era it was built in, its shell unchanged over the decades.

The control room is avocado-green, laid out like a horseshoe. Pressure gauges, buttons and lights cover every surface, while bright red and green phones remain on permanent stand-by at the central desk.

Even in this room, though, one of the most secure in the entire country, coronavirus has a presence.

Staff are masked and the small personal radiation monitors that the team must carry have signs alongside them warning that hands must be washed before their use.

STV News

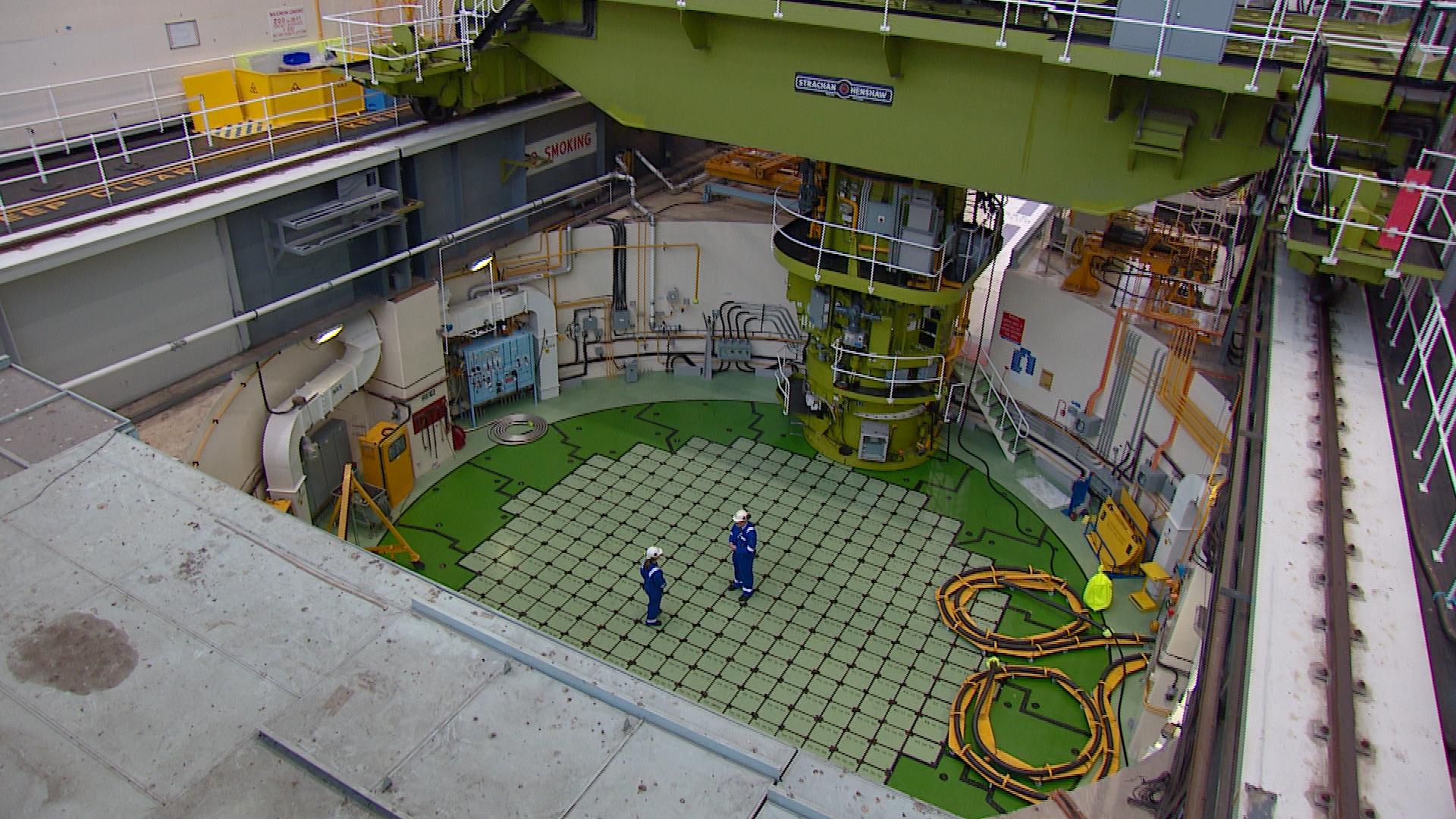

STV NewsIn another part of the plant, a bold geometric-shaped viewing platform hangs suspended over pipes that run like a central nervous system through the station, the workers far below miniscule from the sheer height.

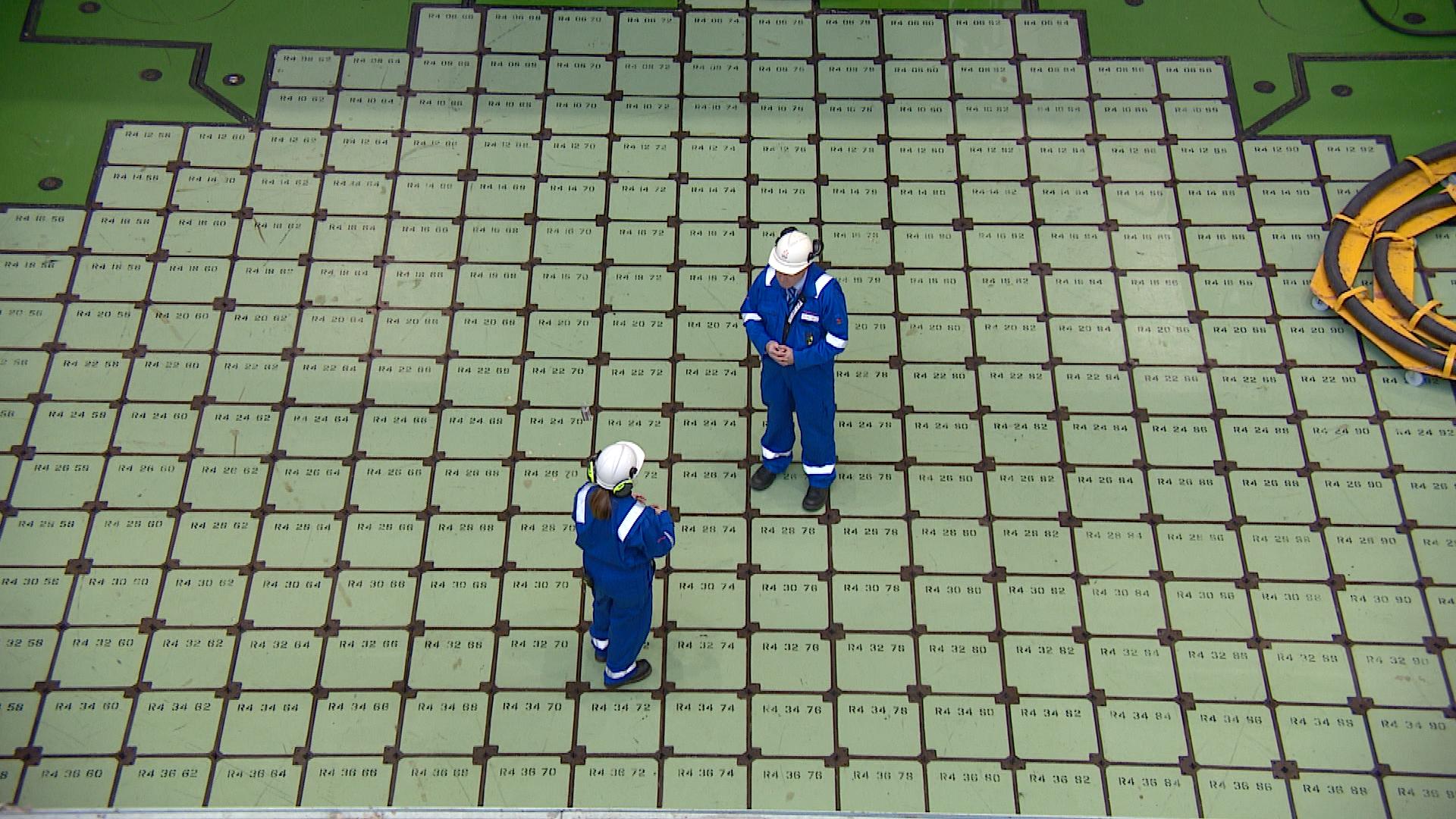

At the station’s proverbial heart, nuclear reactor four is an imposing sight. It is this final reactor which marks the official shutdown of the station, with reactors one to three already ceased.

STV News

STV NewsIn the nuclear core of reactor four, neutrons collide with uranium atoms, splitting them. This split releases neutrons from the uranium that in turn collide with other atoms, causing a chain reaction.

The reactor core itself is ten metres high and weighs around 1400 tonnes, about the same as 110 double-decker buses.

STV News

STV NewsThe chain reaction in reactor four is controlled with “rods” that absorb neutrons.

There are usually around 80 control rods in a reactor such as this, but it takes only 12 of them to actually shut the reactor down.

The plant will then enter a defueling stage, removing all of the nuclear fuel from the reactor and sending it to Sellafield for safe storage.

EDF, which runs Hunterston and Torness – Scotland’s other nuclear plant in East Lothian – has confirmed that staff who wanted to stay on will undertake the defueling, while others have been moved to different sites or taken retirement.

‘I wanted more’

Hunterston B maintenance manager Dougie Graham has been working at the plant since he was a teenager.

“When I was 15 years old, I came here for school work experience and at that point I decided this was the place I wanted to work,” he said.

“As soon as I walked in, I was in awe at the sheer size of the place, the workforce, the team work and I went away knowing I wanted to experience more.”

He’s now been at the station for 25 years.

“What’s not changed is the community feeling,” he said. “I’ve grown up on this site and we’ve been preparing for this for two years. There’s an element of sadness, but today’s a day of pride.”

STV News

STV NewsHunterston’s closure, earlier than originally planned but still beyond the plant’s initial estimated lifespan, marks the end of a chapter in Scotland’s nuclear history. Torness is also preparing for shutdown.

Hunterston originally had a design life of 25 years, lasting 46, though not without concerns. Cracks in its graphite cores forced its temporary shutdown between 2018 and 2019.

STV News

STV NewsLife beyond nuclear

The closures of Hunterston B and soon Torness mark a significant point in Scotland’s energy journey as reliance on renewable energy from wind and water take over.

In 2011, renewable technologies generated around 37% of national demand. By 2020, this figure had risen to 97.4%.

The Scottish Government has been vocally opposed to new nuclear plants, though the UK Government has continued to invest in the likes of Hinkley Point C.

Due to open in 2026 at a cost of £23bn, it is expected to provide electricity for six million homes.

Along with Hinkley, Westminster is also backing new small modular reactors (SMRs) being developed by Rolls-Royce.

Scotland has instead placed its focus on renewables, storage, hydrogen and carbon capture.

STV News

STV NewsThe differing approaches between Scotland and England mirror a similar story in Europe, with countries such as France continuing to invest in nuclear with their neighbour Germany in complete contrast and on course to switch off its remaining three nuclear plants by the end of this year.

In Scotland, the closure of the country’s last standing nuclear facilities continues. The final cloud of steam is expected to rise above Torness on its shutdown in March 2028.

‘Increasingly unreliable’

Environmental campaigners said the final shutdown of Hunterston B – which started producing electricity 45 years and 11 months ago – was “inevitable”.

Lang Banks, the director of WWF Scotland, said the plant had become “increasing unreliable”, arguing that growth in renewable energy means nuclear power is no longer required.

Mr Banks said the “repeated failure to solve the problem of hundreds of cracks in the graphite bricks surrounding the reactor core means the closure of Hunterston B was inevitable”.

He added: “Thankfully Scotland has massively grown its renewable power-generating capacity, which means we’ll no longer need the electricity from this increasingly unreliable nuclear power plant.

“As the expensive and hazardous job of cleaning up the radioactive legacy Hunterston leaves in its wake now begins, Scotland must press on with plans to harness more clean, renewable energy.”

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country