Families affected by dementia have described cuts to vital care services across Scotland as a “devastating blow” to the people who rely on them.

Alzheimer Scotland has warned that the country is “sleepwalking” into a dementia care crisis, as day centres, respite programmes and support groups for tens of thousands of people are being scaled back or closed down.

Research by the charity found cuts worth nearly £154m are being proposed to services for older people and community care.

For people like Tommy Mclean, a 75-year-old from Dumbarton living with dementia, these services are a lifeline.

The retired financial services professional first noticed something wasn’t right when he began to feel “forgetful and depressed” in his mid-sixties.

He was eventually diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia after experiencing an episode on holiday in Tenerife with his wife, Carol, in 2016.

Since his diagnosis, Tommy says he has withdrawn from social life.

“I don’t have the same zest for life that I used to have,” he said. “I used to go out for dinner with friends. I don’t do that anymore. I don’t feel comfortable.

“Family invite us over to stay with them, but it just doesn’t appeal to me anymore. I love my grandchildren, my son, my wife, but there’s something that tells me I’d rather be at home watching the news. That’s what interests me now.”

Carol added: “The world has become smaller. I still love social events, but Tommy doesn’t want to go.

“It’s taken us time to understand you can’t persuade someone with dementia. Their mind is made up. No matter how disappointed you are, you have to go along with it.”

Frontotemporal dementia affects the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain, often leading to changes in behaviour, personality and language.

Medication has helped Tommy manage the condition, but he acknowledges how different life has become.

“I know I’ve changed. It’s not for the better – but life is such. You’ve got to get on with it.”

STV News

STV NewsCarol says one of the hardest parts has been the change in how people interact with her husband.

“We told everyone so they would understand, but I feel it was the wrong thing to do. People treat Tommy differently now. Even medical staff often speak to me instead of him.

“But Tommy can still understand, still hold a conversation. He’s fortunate in that way. It’s not vascular dementia, but it comes with serious challenges.”

One place that has helped Tommy is Alzheimer Scotland’s Dementia Resource Centre in Clydebank, where he attends a day service. He also sings in the One Voice choir, a dementia-friendly singing group.

“When we go in, we have tea and toast, then a bit of lunch,” Tommy said. “I’ve got quite a few chums there. It brings you out of yourself.

“The staff are excellent people. They know what they’re doing, even with people more advanced than me. I can only praise them to the highest.”

But like many similar services across the country, the day care centre Tommy attends is under threat of closure due to local authority funding cuts.

“To hear that we might lose this is devastating,” said Carol. “Carers won’t be able to cope. If we lose this, what’s going to happen to our loved ones? Where will they go?”

Carol says the service not only benefits Tommy but also gives her vital time for herself to go shopping or meet friends for coffee.

“When I pick him up from the day centre afterwards, he’s like a different man. He’s so animated and can’t wait to tell me about his day.”

Both Tommy and Carol believe the loss of such services would be catastrophic.

“It would have an adverse effect on me,” said Tommy. “I’ve been going for a few years now. I’ve made friends, but I’ve also been to funerals. Dementia is a killer disease.

“If the centre closes, I’ll lose friends. I may never see them again.

“I’ll lose contact with the staff who are excellent. I just don’t know what’s ahead.

“I have a good wife who looks after me – she’s an unpaid carer. Like so many others.”

STV News

STV NewsTommy and Carol are not alone. Other families across Scotland are already experiencing the fallout of service changes.

Ann McGill and Evelyn Meechan were told their relatives would be moved from the Hatton Lea specialist dementia unit to a new facility at Udston Hospital. But that plan was scrapped and no suitable replacement was offered.

“They told us Udston was going to be the new concept for dementia care,” said Ann. “We saw the plans. Then they pulled the plug. My mum wasn’t suited to mainstream care, but we had nowhere else to send her.

Evelyn added: “It just feels like, ‘How much money can we save?’ That’s not how people with this illness should be treated.

“He continues to deteriorate. It’s hard mentally and physically trying to deal with this.”

Across areas such as Edinburgh, Fife, Falkirk and Aberdeen, tens of millions of pounds in savings are being proposed – mostly from services like day care, home support, respite and older people’s care.

While not all cuts are dementia-specific, many will directly impact people with the condition and their families.

Supplied

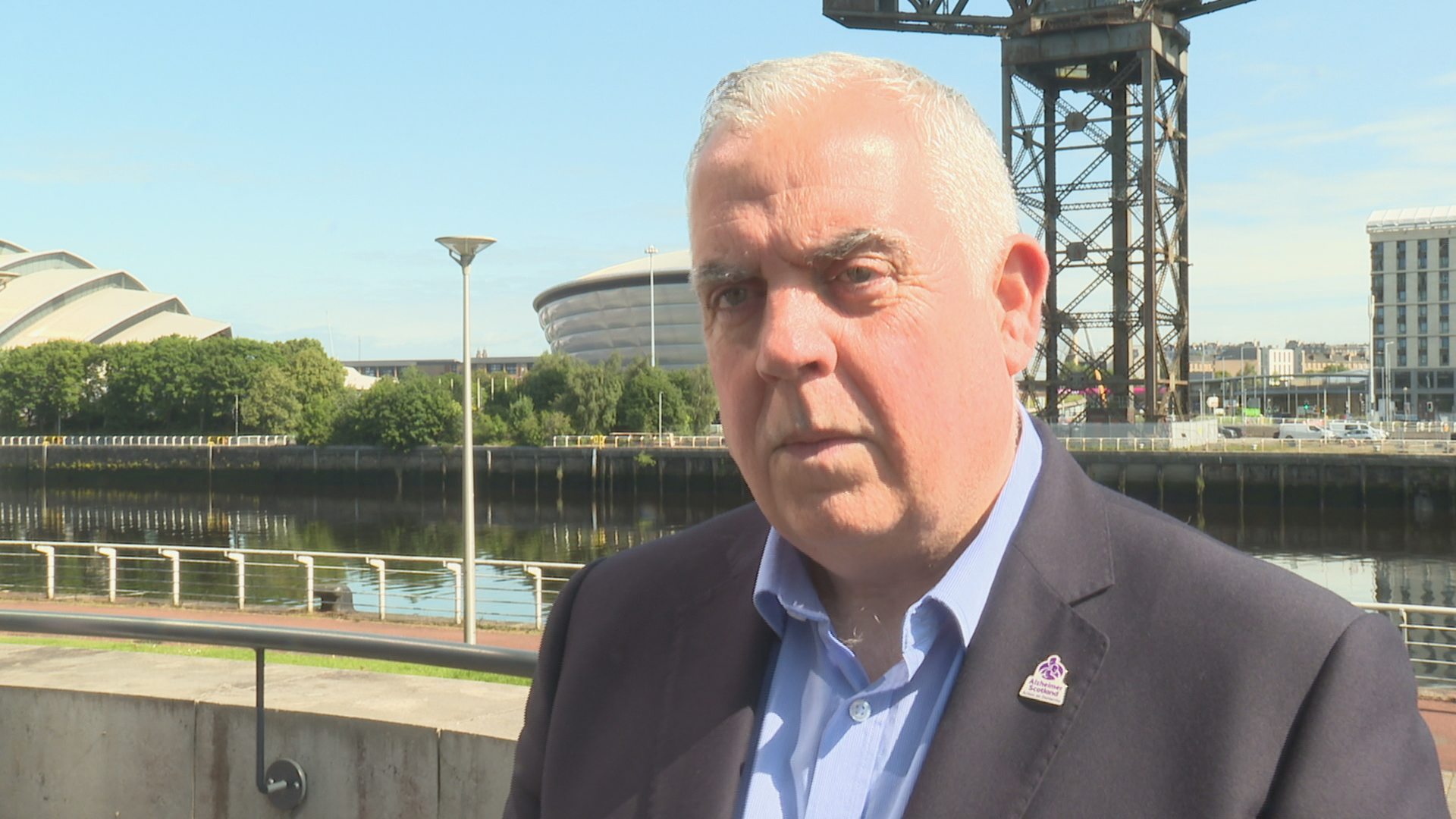

SuppliedAlzheimer Scotland chief Henry Simmons warns hundreds of thousands will be affected by the cuts and has called on the government to “take leadership.”

“We need a guaranteed national dementia care pathway. If the government leave things to local budgets, then they are letting people with dementia down.

“We’re seeing specialised dementia services, which tend to be highly therapeutic and smaller scale, becoming really targeted for cuts because they’re going to take that funding and absorb it into bigger services, not dementia specific.

“There’s no real logic to some of these decisions. We know some services for 25 years, seven days a week, high-quality care – but because it costs £300,000, that’s tagged as a potential saving.

“That’s completely scandalous, that we make a decision about a service of that nature based on a budget figure.

“There’s no other condition where the care pathway is this fragile. It’s entirely a postcode lottery. That would never be allowed with any other condition. This needs to come to an end.”

STV News

STV NewsThe Scottish Government says it is investing £4.35m this year as part of its 10-year Dementia Strategy, working with Alzheimer Scotland and other partners.

But families say change is needed now.

Carol said: “We see the psychiatrist regularly, but with frontotemporal dementia, there’s no way of knowing when something will suddenly change.

“It might get to the point where I can’t cope. Unpaid carers are not trained. We’re just doing our best. It’s really scary.”

Tommy added: “The axe is bound to fall sooner or later. If this place closes, it will be a blow. I don’t know what’s in front of us.”

Claire Rae, chief officer, University Health & Social Care North Lanarkshire, said: “When we were served notice to leave Hatton Lea care home we reviewed our existing Mental Health facilities to determine where would best meet the complex needs of the patients.

“Patients in the HBCCC service are reviewed regularly to see if this is the most appropriate care for them or if their needs can be better met in a homelier environment such as a care home of their family/carer’s choice.

“The number of patients who would be remaining in the HBCCC service was low enough that the service could be hosted at Clelland Hospital, an existing older people’s Mental Health hospital, where staff already have the appropriate skillset.

“Clelland Hospital is a secure, safe environment with 24-hour staff support which offers private en-suite rooms.

“These are in single-sex wards, which many families told us were important factors for them. There are also separate, comfortable dining and lounge areas for men and women, and dedicated garden spaces for patients and visitors.”

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country