What links a native breed of cow, the latest satellite technology, and ancient oak woodland?

They’re all part of a project to restore one of Scotland’s largest nature reserves – Glen Finglas.

Spanning an area the size of Greater Glasgow, Glen Finglas was bought by the Woodland Trust in 1996. Before that, it was a sheep farm where much of the natural grass and plant life had been overgrazed.

Fast forward almost three decades, and a dramatic transformation has taken place.

At the centre of this change is an unlikely star – Luing cattle. This breed, a mix of Highland and Shorthorn beef cows, thrives on the hillside.

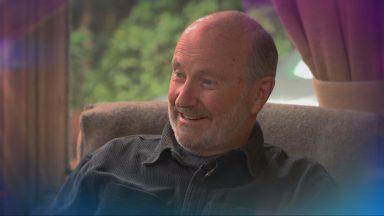

STV News

STV News“The Luing Cow being a very good converter of the rough forage and perfect for going out in the woodland that is being restored, with their hooves breaking up the soil,” said Janet Pringle, the farm manager working with the herd.

“The difference in the glen can definitely be seen. The cattle are in and about those woods as the trees grow and get to a height where there not going to be harmed by the cows.

“They will be contributing to that restoration going forward.”

Janet, along with land managers, uses GPS technology to manage the cattle’s movements. Virtual fences created by GPS collars buzz if the animals stray beyond set boundaries.

These virtual fences can be adjusted at the tap of a screen, moving the herd to avoid overgrazing and allowing targeted grazing in specific areas.

“Those collars let us create a fence. If we put in a traditional livestock fence, you spend the money, you put the fence in, that’s it. You can only work within that.

“The collars give us greater flexibility to move projects about, increase or decrease numbers and move about the estate in a more free way than what we would with traditional fencing.”

As plant life has flourished, so too has the glen’s wildlife. Pine martens, red squirrels, otters, golden eagles, and wild trout all thrive here – signs that the restoration is working.

Black grouse have also made a comeback, with a stable population now reported.

STV News

STV NewsDeer, however, present a challenge.

Estate manager Hamish Thomson said: “They belong here. They are the primary grazers and they belong in the woods. They help to manage the landscape, and they keep the green bits green we don’t want trees everywhere.

“We’ve got these wildflower meadows, and we need them free of trees.

“But with no natural predators that are preventing some regeneration, so we need to work hard on the deer and reduce the population for a period of time to help that regeneration come through.”

With nearly 70 square miles of new woodland created and more than one million native trees planted, Glen Finglas is a vast site. Managing the relationships between various stakeholders is a key part of the ongoing work.

“Glen Finglas and the Great Trossachs forest is a great example of what can be achieved over time. Our job now is to work with stakeholders to supercharge this as it goes forward” said Simon Jones, director of environment and visitor services at Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park.

“Farmers completely underpin this. They will deliver nature restoration in many ways and farmers work closely in terms of their network; often one person taking a first step can lead to others getting onboard.”

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country