A nation-wide outbreak of E.coli has led to dozens of people being admitted to hospital with 13 recorded cases in Scotland, but what has sparked the surge in infections?

Half of the affected patients in Scotland have been admitted to hospital since the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) identified what it believes to be a “single outbreak” since May 25.

“The disease we’re really concerned about right now is then shigatoxigenic E.coli – STEC for short… It can be very a serious infection and can unfortunately lead to fatalities and we have seen that in Scotland”

Dr Nicola Holden, professor of food safety at Scotland’s Rural College

Public Health Scotland said cases are being seen in all age groups but most are among young adults, with the tally of 13 recorded in Scotland as of June 4.

While experts said it is “most likely” the outbreak can be linked to food distributed nationally, investigations are under way by public health bodies to identify the source.

It comes after a person in Scotland died following a cheese-linked outbreak of E.coli that infected at least 30 people across the UK in December.

What is E.coli and how does it spread?

iStock

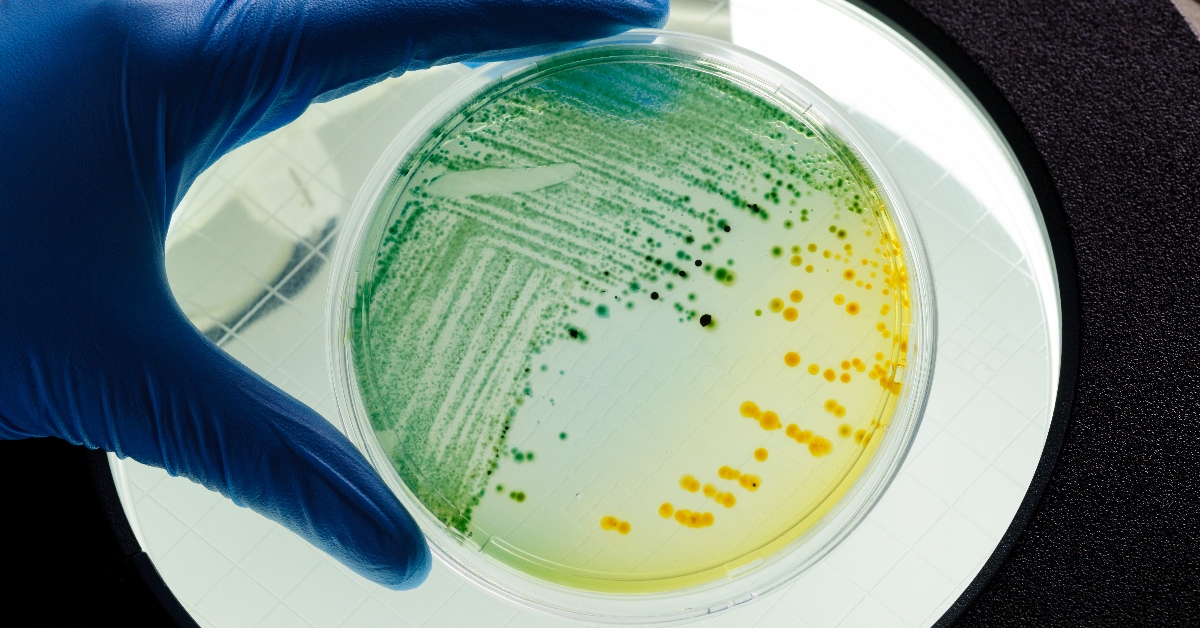

iStockE.coli are a diverse group of bacteria that are normally harmless and live in the intestines of humans and animals.

However, some strains produce toxins that can make people very ill, such as STEC.

Experts said it is “most likely” the outbreak is linked to a nationally-distributed food item or multiple food items.

While public health agencies across the UK including the Food Standards Agency (FSA) are working to identify the specific cause of the outbreak, it is currently unknown.

STEC can also be spread by close contact with an infected person, as well as direct contact with an infected animal or where it lives.

The UKHSA said there was currently no evidence linking the outbreak to open farms, drinking water or swimming in contaminated sea, lakes or rivers.

Dr Nicola Holden, professor of food safety at Scotland’s Rural College told STV News: “We’re more aware of E.coli because of some of the issues with water and sewage.

“Because E.coli is normally carried by humans, it’s an indicator of sewage contamination.

“In terms of the outbreak we’re seeing now, we do have quite a large outbreak compared to normal STEC outbreaks. But we do tend to see them during the summer months.

“It is a challenge (to trace source of the outbreak).

iStock

iStock“Because the bacteria are associated with cattle, they do come from the food chain from beef and from dairy production but can also come from vegetables for example.

“There are some of the usual suspects, these will be under investigation.”

She added: “If you are going to have a barbecue, make sure the meat is thoroughly cooked, it is the right temperature and make sure you store food appropriately in the fridge as well.”

What are the symptoms and side effects of E.coli?

People infected with STEC can suffer diarrhoea, and about 50% of cases have bloody diarrhoea.

Other symptoms include stomach cramps and fever.

Symptoms can last up to two weeks in uncomplicated cases.

Some patients, mainly children, may develop haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) which is a serious life-threatening condition resulting in kidney failure.

A small proportion of adults may develop a similar condition called thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura (TTP).

Dr Holden said: “The disease we’re really concerned about right now is then shigatoxigenic E.coli – STEC for short.

“That can cause a reasonably long-term disease. It doesn’t just last a couple of days.

“If its just diarrhoea, it will clear in a few days but it can go along to cause more serious symptoms in some people that will last longer.”

She added: “The STEC version is much more serious than some of the other E.colis.

“This particular group of people that are affected tend to be very young. STEC will cause more serious disease in younger people.

“If they go on to develop the serious type of disease that affects the kidneys then intensive care would be required.

“It can be very a serious infection and it can unfortunately lead to fatalities and we have seen that in Scotland.”

What action should be taken to prevent infection?

Jim McMenamin, head of health protection at Public Health Scotland said it advises regular hand washing using soap and water, particularly after using the toilet and before preparing food.

Disinfectants should also be used to clean surfaces that may be contaminated.

Those experiencing symptoms should avoid attending schools, workplaces or social gatherings until at least 48 hours after their symptoms have passed.

Members of the public are being advised to call NHS 111 or contact their GP surgery if they are worried about the following:

- A baby under 12 months

- A child who stops breast or bottle feeding while they are ill

- A child under five who has signs of dehydration such as fewer wet nappies

- Older children or adults still have signs of dehydration after using oral rehydration sachets.

Help should also be sought if people are being sick and cannot keep fluid down, if there is bloody diarrhoea or bleeding from the bottom.

Diarrhoea that lasts more than seven days or vomiting for more than two days should also be investigated.

Trish Mannes, incident director at UKHSA, said: “If you have diarrhoea and vomiting, you can take steps to avoid passing it on to family and friends.

“NHS.uk has information on what to do if you have symptoms and when to seek medical advice.

“Washing your hands with soap and warm water and using disinfectants to clean surfaces will help stop infections from spreading.

“If you are unwell with diarrhoea and vomiting, you should not prepare food for others while unwell and avoid visiting people in hospitals or care homes to avoid passing on the infection in these settings.

“Do not return to work, school or nursery until 48 hours after your symptoms have stopped.”

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country