A Scottish mum-of-three was diagnosed with cancer after her grandmother was exposed to a pregnancy drug linked to a number of health complications.

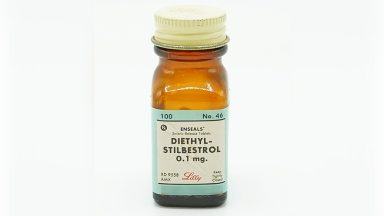

Diethylstilbestrol, commonly known as DES, was given to an estimated hundreds of thousands of women between the 1940s and 1980s in the UK.

Health experts believe that if the drug were taken during pregnancy, effects could have been passed down to future generations.

It was supposed to prevent miscarriages, but has been found to have led to cancer and infertility among other health complications for the children of the women who took it.

Have you or someone you know been impacted by DES exposure?

Tell us your story.

Kimberly Brown noticed a growth that never went away for a year, before a gynaecologist told her she had “never seen anything like it”, but suspected it was cancer.

She was diagnosed with a rare form of clear cell carcinoma vaginal cancer in her early 30s, and was told by doctors it may have been linked to a drug her mother was given.

But Kimberly believes it was actually her grandmother who had been exposed to DES while pregnant with her mum in the 1960s.

“I hadn’t processed much of it at first, I didn’t know my cancer was caused by that drug,” she told STV News.

“I was never told it was caused by anything else, and finding the DES support groups, I didn’t feel as alone as I had.

“The cancer changes your whole life.”

Following an ITV News investigation, the Medicines Regulator (MHRA) admitted it falsely claimed that doctors were advised to stop using the drug in pre-menopausal women in 1973.

The drug was banned in the United States in the 1970s after studies linked the use of DES with breast, cervical, and vaginal cancers.

Campaigners are calling for anyone who may present with potential symptoms of having DES exposure passed down from their mothers to be fully screened.

There are fears that GPs in the UK, including in Scotland, may not be fully aware of the drug and what to do if a patient presents with health implications caused by the drug.

The mum-of-three from Balquhidder said women across the country trusted doctors and GPs, only to be given something they shouldn’t have been exposed to.

She said: “There’s clinical negligence here. They knew it was causing issues and never stopped it. It is good that they have acknowledged it.

“We put a lot of faith in our doctors. We trust that they know better than they do – we take it blindly sometimes.”

On the support group, Kimberly added: “We want recognition for what’s happened.

“My main message to everyone is to keep on it, you know your own body. If it doesn’t feel right, keep your GPs informed and take your health seriously.”

What was DES used for in Scotland?

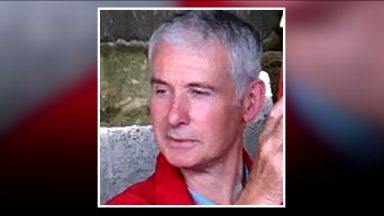

Dr Wael Agur

Dr Wael AgurDr Wael Agur, a consultant urogynaecologist in Glasgow, said the drug was used for a variety of reasons in Scotland, mainly to stop breast milk if a mother’s baby had died.

It was also prescribed to unmarried mothers who were forced to give up their babies.

Women also took DES to stop vomiting during the early weeks of pregnancy, and to prevent miscarriage, especially if bleeding developed in the first few weeks.

Research being conducted in the US is screening hundreds of thousands of women to see if the effects have been passed down to granddaughters.

In 2011, a study found cumulative risks in women exposed to DES were higher compared to those not exposed for infertility, spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery and loss of second-trimester pregnancy.

Dr Agur told STV News: “It is historical, but we are seeing this in the second generation, and there is some research now to suggest that the third generation may also be affected, but the research is still ongoing.”

“It’s going to be several years, at least another decade, before we see the full-blown picture of this,” he added.

What impact did DES have on those prescribed it in Scotland?

Dr Agur said that the implications of DES can be missed because they develop before and after the screening age.

He said: “The main health implication was increased risk of breast cancer in their daughters. Women who had DES in the ’60s and ’70s may have been pregnant with baby girls.

“Those girls are called the DES daughters, and this is where the main health implications are.

“The types of cancers that are caused by the DES are different from those that we screen for in the current screening programme.

“The current screening programme, for example, starts at 25 and stops at 65. However, the current cancer can develop in younger women, before the screening age starts, and in older women after the screening age stops.

“The duration of screening needs to increase, and also the method of screening. There needs to be additional tests, because the standard screening tests are less likely to pick this up.”

He added: “England and Australia have made some advances in this. Australia has modified its screening programme to be customisable to those who had the DES exposure.

“Women with DES exposure get screened for longer and get better screening testing in places like Australia, but that is not happening in Scotland.

“We need improved awareness among doctors and women. If doctors don’t know about it, they won’t be able to pick it up.

“The additional screening programme will need to be prescribed for those at high risk, or those we already know have been exposed. We have a duty to these women.”

Medical regulator admits ‘inaccurate’ statements

The Medicines Regulator (MHRA) admitted it inaccurately claimed that doctors were advised to stop using the drug in pre-menopausal women in 1973.

A spokesperson for the MHRA said: “Our sympathies are with those harmed by the historic use of Diethylstilbestrol (DES). We apologise for this error and for any distress caused to patients and the public.

“At the time of the communication in 1973, usage in pregnancy in the UK was considered to be much lower than in the US, which, coupled with the lack of UK cases of affected children, led to the conclusion that communicating to doctors on the available evidence was sufficient.”

It added: “There has been a step change in reporting and record keeping since this time and today’s regulatory frameworks are significantly different, with much stricter post-authorisation monitoring allowing for earlier identification and action on emerging safety issues.

“The MHRA keeps the safety of all medicines under continual review.”

Clare Fletcher, partner at lawyers Broudie Jackson Canter, who is representing UK DES victims, has called for a full-scale inquiry:

She said: “This is a government failure and a systemic failure. A state compensation fund should be made available for those men and women who have been through unspeakable trauma, infertility, and cancers.”

Health secretary Neil Gray said: “I have the utmost sympathy for the women who may have been harmed by stilbestrol.

“The regulation of medicines is reserved to the UK Government, meaning any further investigation into stilbestrol would ultimately be a matter for them to consider.”

Have you or someone you know been impacted by DES exposure?

Tell us your story.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country