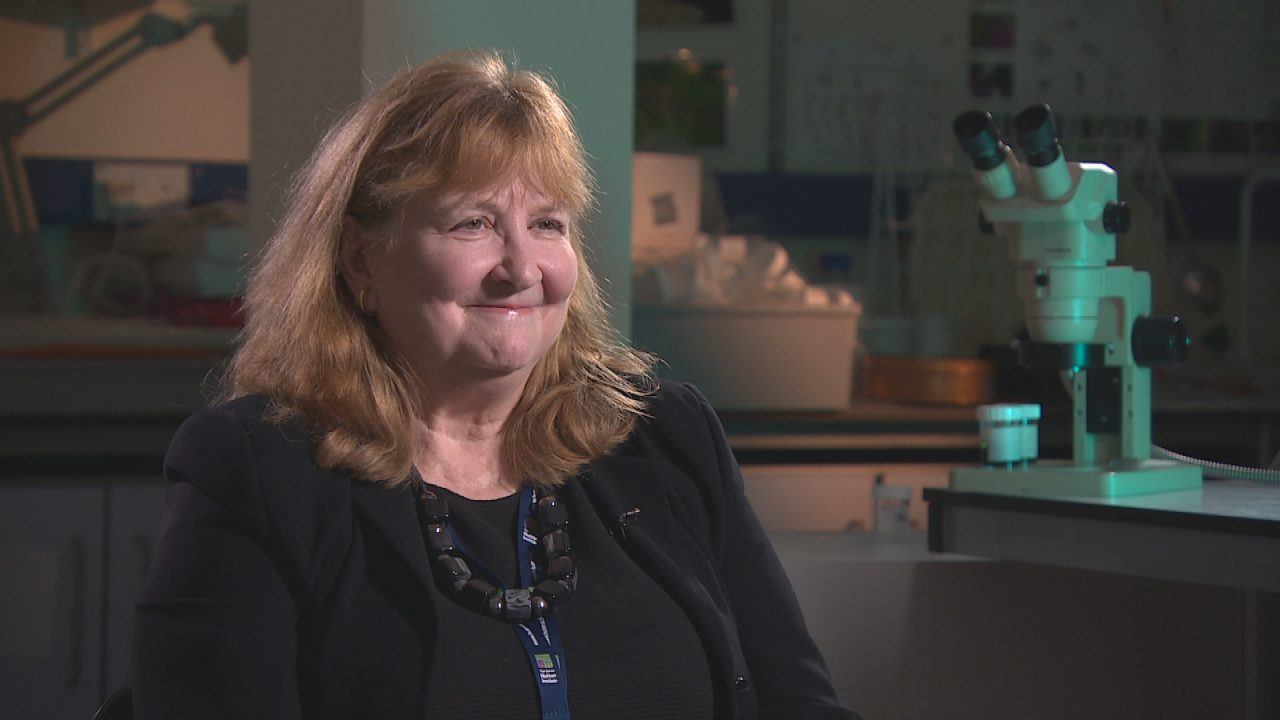

Professor Lorna Dawson’s journey from the fields of rural Angus to the witness stands of Scotland’s most high-profile murder trials is a remarkable one.

It is rooted, quite literally, in her love of soil.

“I came from a family where farming was in their blood,” Dawson told Scotland Tonight.

“My mum took me out to identify the different wildflowers. My dad took me into the countryside in the Land Rover to look at fields and the different soils.

“I loved being outside. I loved looking at the differences you get in different soils and the different types of habitats.”

That childhood fascination would later blossom into a pioneering career in forensic soil science.

It’s a discipline Dawson helped transform from a niche practice into a credible and respected tool in the fight against crime.

Around 2005, Dawson – then working at the Macaulay Institute for Soil Research – got a call that would change everything.

The National Crime Agency wanted to know whether soil could be analysed to help solve a drugs case. They specifically needed to ascertain the origin of soil found on a spade seized from a suspect.

“We ran this suite of analyses and compared that data with our database of soils,” she explained.

“I went with the officer from the Grampian Police to the site where I thought it had come from. Very quickly, they brought the dogs in, and the dogs found the drugs that had been buried in that woodland.”

It was a pivotal moment.

“We realised then that the methods we used could be applied to soils to help work out where they come from,” said Dawson.

Supplied/Scotland Tonight

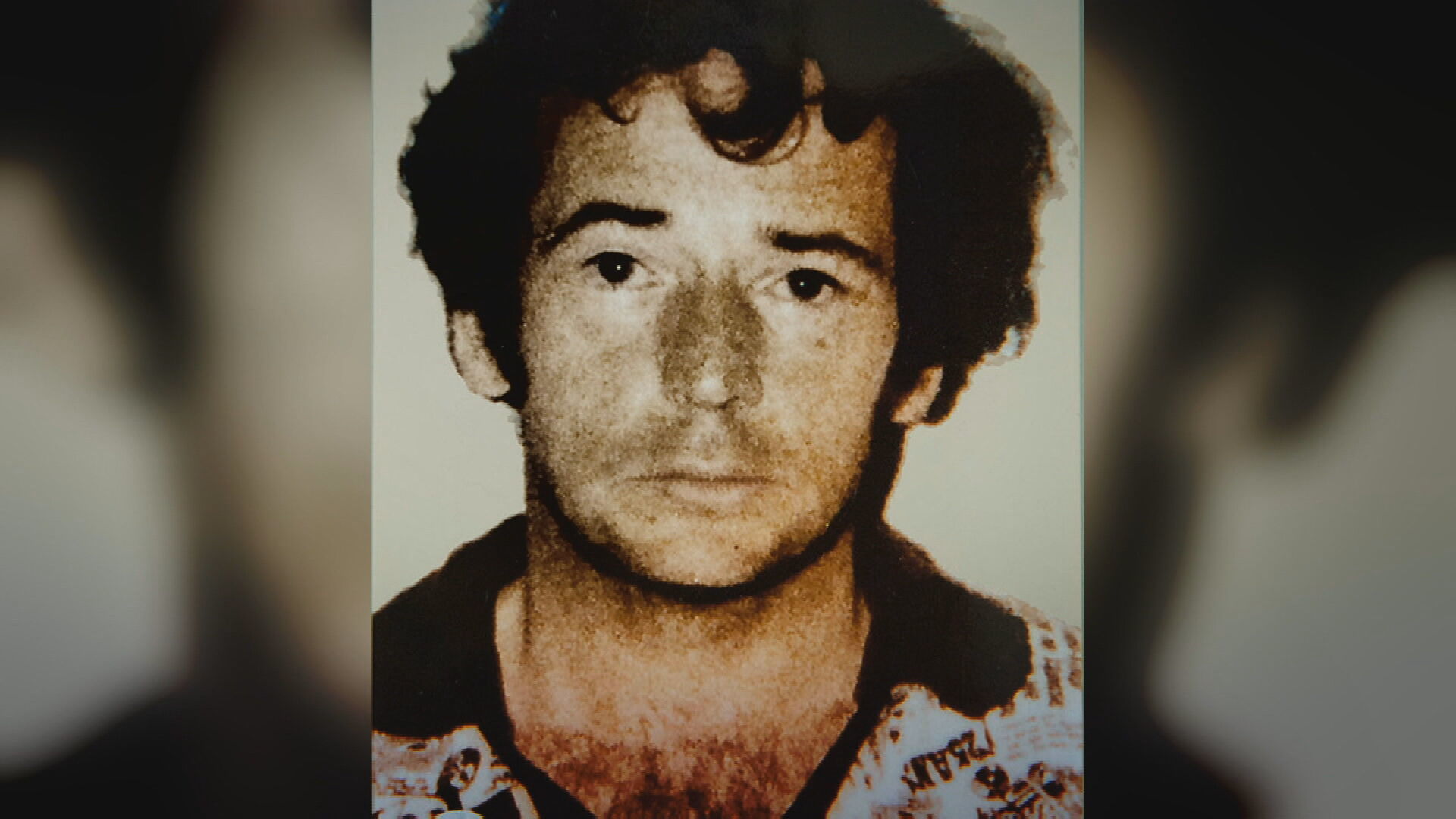

Supplied/Scotland TonightOne of the most significant cases she became involved in was the retrial of the so-called World’s End murders – the 1977 killings of 17-year-olds Christine Eadie and Helen Scott.

“That particular case will always stay with me,” she said. “I’d just gone off to university from the safe rural environment of the countryside of Angus to the big city of Edinburgh. I was 17 – the same age as the girls who were found dead.

“Young girls like myself were terrified to go out alone. We wouldn’t go to pubs unless we were all together. There was a real sense of fear that continued for many years.”

More than three decades later, Dawson’s expertise proved crucial. Police asked her to analyse soil samples that had been collected from Helen Scott’s feet in 1977 and carefully preserved.

“We could take those samples and analyse them…to help the police work out where Helen had been prior to her death,” Dawson explained.

“We developed an organic fingerprint, a distinctive profile of the landscape. We were able to see not just one, but two different materials. One from the wheat field where she was found and another from a grass verge.”

STV News

STV NewsThat evidence helped prosecutors finally convict Angus Sinclair in 2014, under new double jeopardy laws.

“It really showed that we could help the criminal justice system with this type of problem,” she reflected.

After the trial, Dawson received a letter from Helen’s brother, Kevin Scott.

“He said he had been overwhelmed to see how much work everyone had put in to bring justice for his sister. I treasure that letter because that’s what really makes it all worthwhile.”

Throughout her career, Dawson has remained committed to objectivity.

“We try not to know too much about the case context until after we’ve given evidence in court,” she said. “We code each sample that comes in to minimise any potential bias in interpretation. We produce facts and opinions for the courts.”

But even with that detachment, some cases have hit home.

“There was a case in England, a little three-year-old child had been killed by his stepfather. I was examining the pyjamas he was wearing to recover trace evidence of soil and vegetation.

“They were the exact same pyjamas my grandson had. I had to tell my daughter not to put him in them anymore.

“This was a little boy, an infant, and these pyjamas were the last thing he’d been wearing, like lots of other little children, before he was killed by someone he should have been able to trust.

“That really stayed with me.”

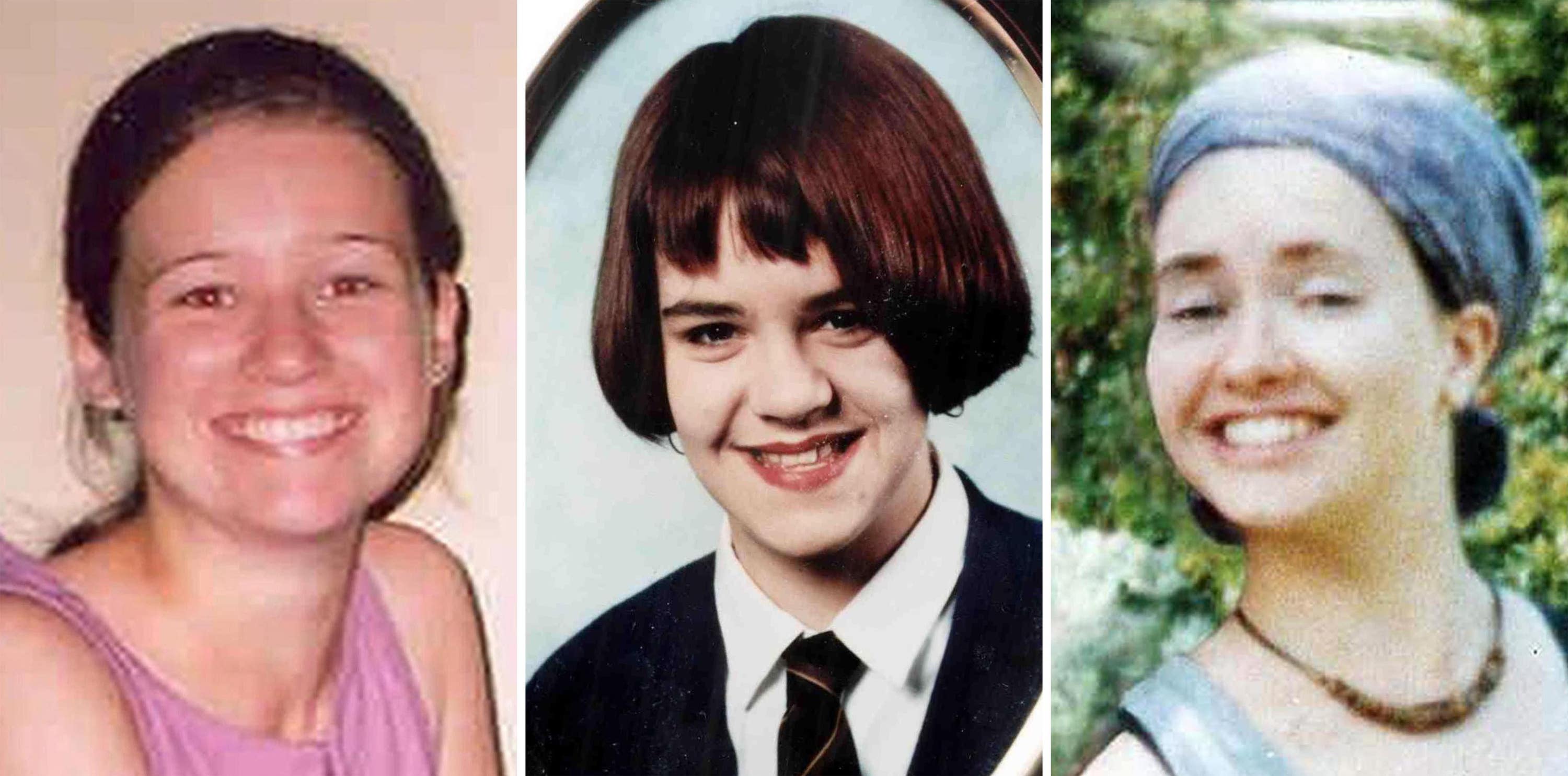

Dawson also worked on the case of Karen Buckley, the young Irish student murdered in Glasgow in 2015.

“My daughter had just gone off to university,” said Dawson. “Stranger murders are very rare, but by the grace of God, you can meet the wrong people. I think as a Scottish people, we felt very responsible and sad that she’d come to harm in our country.”

Her analysis of soil found on Alexander Pacteau’s boots and car tyres helped police identify key locations where he had driven after abducting Buckley, including the remote area at High Craigton Farm where her body was eventually discovered.

This forensic link played a significant role in building the case against Pacteau and securing his conviction.

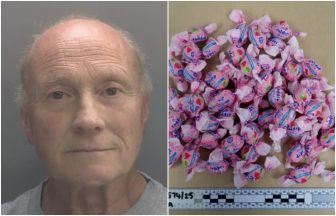

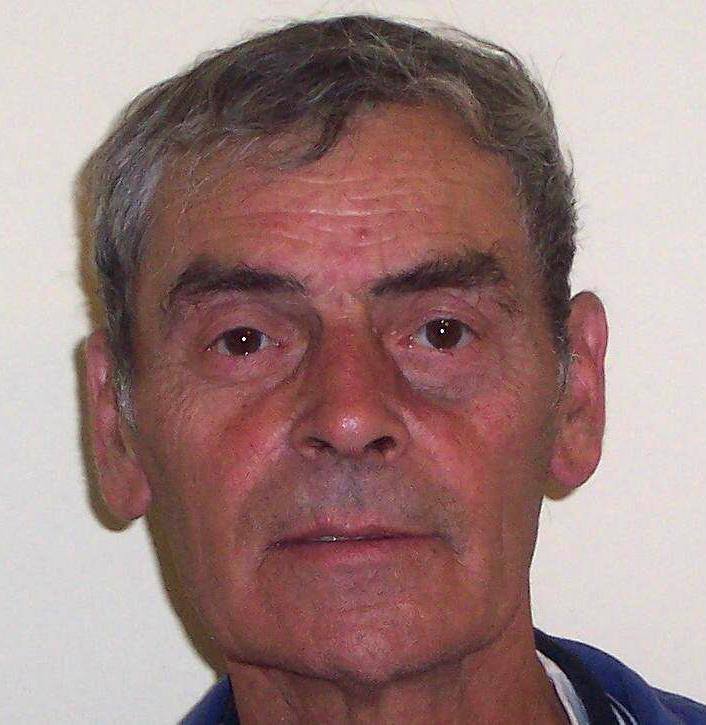

Among her most high-profile cases, Professor Dawson played a crucial role in the investigation into Peter Tobin, the convicted murderer linked to the deaths of Vicky Hamilton, Dinah McNicol, and Angelika Kluk.

Tobin is widely regarded as one of Scotland’s most notorious serial killers.

Police Scotland

Police ScotlandDawson’s forensic soil analysis was instrumental during the search for Vicky’s remains following the teenager’s disappearance in 1991. Seventeen years later, her body was found buried in the garden of Tobin’s former home in Margate, Kent.

Soil found on bin bags used to wrap Vicky’s remains was compared to earth samples from Tobin’s former home in Bathgate.

That helped to confirm the body had been buried there and then moved and reburied when Tobin moved 470 miles away to the south of England – a key detail in reconstructing the timeline of events.

Police Scotland

Police ScotlandDawson’s meticulous work helped detectives build a stronger case against Tobin, linking him not only to the crime scene but also to efforts to conceal his victims.

The case demonstrated the power of environmental forensics in historical investigations, especially when other evidence had long since degraded.

Dawson’s contributions haven’t just supported prosecutions. Her work also helped in searches, such as that for Ben Needham, the British toddler who disappeared on the Greek island of Kos in 1991.

Forensic analysis of a child’s sandal recovered on-site revealed the presence of blood and supported the theory that he had been accidentally killed by a digger.

Looking to the future, Dawson believes soil science holds even more untapped potential.

“We’ve got the inorganic minerals which tell us about geology, the organic part which tells us about habitat, and the biological part – that’s the DNA,” she explained. “Soon, we’ll not only be able to see where a sample came from, but also when someone was at that location.”

She’s excited about the science, but also keen to demystify it.

STV News

STV News“It’s important that we communicate science to make people understand that it’s not a mystery. Science is exciting, very interesting, and very useful,” she said.

“Soil can be used in many avenues – from agriculture to water purification – and also to work out whether material came from the crime scene, or from alternative proposition locations such as the home address of the accused.”

As for the portrayal of forensic scientists on television, Dawson is realistic and has even worked as a consultant on Silent Witness.

“Like a lot of programmes, it’s a mixed bag. Some are very good. Others are entertainment – a way for the public to go into dark places, but safely from their armchair.”

Even as a child, Dawson was fascinated by the dark side.

She said: “I used to read and watch Agatha Christie and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series…but safely, even though you ran up the stairs at night after being immersed in the stories, glancing behind at your peril.”

Thanks to her dedication, passion and scientific rigour, generations of detectives – and victims’ families – have found something more substantial than fiction: Truth, rooted in the earth beneath our feet.

Professor Lorna Dawson is a Principal Scientist and Head of the Centre for Forensic Soil Science at the James Hutton Institute, and one of the UK’s leading forensic soil scientists. Her work has contributed to dozens of criminal investigations across the UK and internationally.

Watch Scotland Tonight: A Conversation with Lorna Dawson on Thursday at 8.30pm on STV and the STV Player.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country