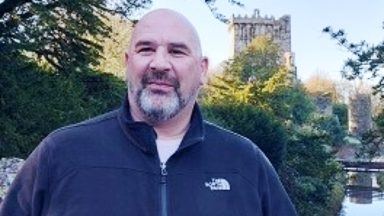

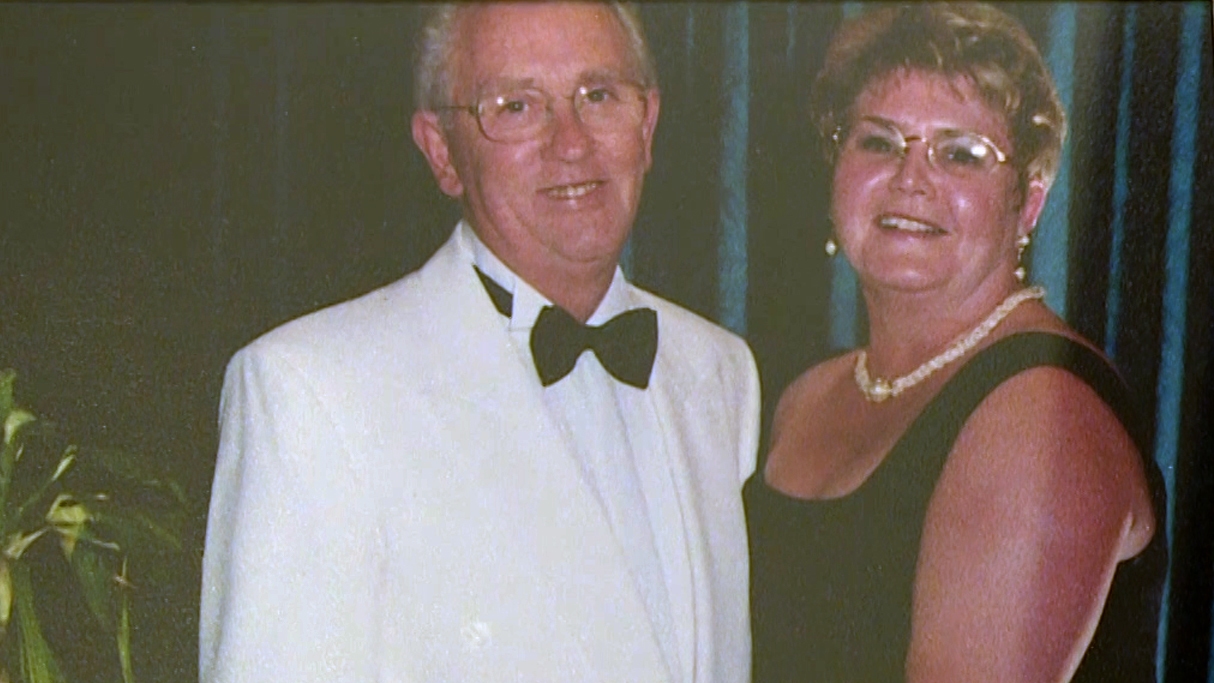

Doreen Borland and her husband Andrew are soul mates. They met working in retail almost five decades ago, and went on to marry and settle in Port Glasgow.

Travelling was their passion – that, and spending time together with family and friends.

But a few years ago, Doreen noticed subtle changes in Andrew’s behaviour. To start with, it was things like forgetting where he had put something or failing to remember a word.

Slowly, though, he became more confused.

“Instead of putting the rubbish bags outside in the bin, they would go in plant pots, in the garden, behind the shed,” she told Scotland Tonight.

“I lost him in Gatwick Airport. Luckily I had his picture on my phone, the police sent the picture round and they [found] him.

“After that, every time we were going out somewhere, I would take a picture of what he was wearing that day.”

STV News

STV NewsDoreen, 74, contacted their GP, who started doing tests every six months. In 2017, a brain scan confirmed that Andrew had Alzheimer’s.

Lockdown in March 2020 then heralded a steep decline in his condition.

Doreen said: “We used to go to an Alzheimer’s café, and get the support there – that stopped. He was due to go to a day centre – that was stopped. We actually became prisoners in our own house.

“He would walk from the front door to the back door constantly, just wanting out. We could go out in the garden, but then I had to be careful because he would be out the back gate and off – as he was one day, when we found him in slippers, no jacket on, in the middle of the road.”

Doreen then made the difficult decision to move Andrew, an RAF veteran who served at Leuchars, into a care home.

STV News

STV NewsThe Erskine veterans’ charity was quickly able to find him a place at its specialist dementia care home.

Doreen said: “To know that he was going out the door for the last time… it was very hard.

“And to come back in, to that chair being empty, the house quiet, clothes in the wardrobe never to be used again.

“I think I hid for about three months, not wanting to speak to anybody. I was absolutely saturated with guilt, of putting him into a home.”

Andrew, 84, is settled now, and Doreen takes comfort in knowing that he’s getting the expert care he needs.

“Andrew’s now laughing, he’s smiling, he’s got company, he’s got a secure garden to sit in,” she said. “I know Andrew will not remember when I leave that I’ve even been there. But that’s okay, I know.

“It was a hard year, a lonely year. But I’m starting to put the pieces together again. I have had a wonderful life and I’ve got to put that into perspective, and remember all the years before, where we had fun, and laughed a lot, and just were together.

“He was my soulmate, he still is.”

‘I thought my life was over’

Margaret McCallion, from Glasgow, was diagnosed with a rare form of dementia seven years ago.

She sought help from her doctor after noticing she was having problems with her memory and doing things which were out of character.

She was just 51 when she learned she had dementia – she thought her “life was over”.

Margaret had worked as an administrator in the NHS for many years, so she was taken aback when she was told she would have to leave her job.

“What I was actually told was that if I had another kind of disease, they might have kept me on at a lower level, but because it was neurological, it was just ‘cheerio’,” she told Scotland Tonight.

“It was a shock for me to stop working.”

STV News

STV NewsMargaret is now an active member of Alzheimer Scotland’s dementia working group, which fights for better awareness and support.

She said: “That certainly gave me back self-worth. Do as much as you can, whatever you enjoy, keep doing it. You know – see the person, and not the disease.”

Margaret, who lives with her sisters and their elderly mother, is trying to make the most of life.

Although her consultant believes she may eventually need treatment, including speech therapy, she has not required it so far.

“It’s more my memory that’s affected than anything else,” she said. “But I keep trying to do things to keep it sharp – brain games or if there’s any quizzes on TV, I like to see how many questions I get right.

“I’m thankful I live in a calm house and I’ve got a lot of great friends and relatives. My sisters have got power of attorney for me. I’m thankful I still know everybody.

“There’s no point sitting wallowing in misery because it doesn’t have to be like that. Although it’s great to still feel independent, I don’t know how much older I’ll get. Every day’s a bonus.”

Scientists ‘very hopeful’

Dementia is an umbrella term for more than 100 different types of illnesses and disease symptoms, including Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia.

There is no cure – but there is hope.

Professor Tara Spires-Jones, of the UK Dementia Research Institute at Edinburgh University, is optimistic about a breakthrough within the next couple of decades.

“Research works, we’ve all seen this with Covid,” she told Scotland Tonight.

“What we’re all trying to do here is come up with something that is truly life-changing, that will change the game, stop the brain from getting worse and maybe even help it get a little bit better. It’s possible within my career, I would say. I’m very hopeful.”

Professor Tara’s team specialises in examining how connections in the brain can become tangled.

It uses donations from the Scottish Dementia Brain Tissue Bank for its work, taking tiny brain samples and looking at individual synaptic connections.

“These are how the brain cells, the neurons, talk to each other… when they die, you lose your ability to think, and learn, and make new memories,” she said.

“What we’re really able to do on a fundamental level is understand changes in synapses and help translate that understanding into a drug that can hopefully rescue them.”

The brain needs a healthy blood supply to make sure it functions correctly.

Vascular dementia, which makes up about a fifth of all dementias, is believed to be mainly caused by blood vessels in the brain going wrong.

A new study, funded by the Alan Turing Institute and British Heart Foundation, is examining blood vessels in miniscule detail, in the hope of finding out more.

The research involves patients going for monthly MRI and eye scans, and cognitive tests, at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary.

Professor Joanna Wardlaw, also at Edinburgh University, is leading the project.

“The problem with the scanning in the brain is that we can’t actually see the blood vessels, so by studying the blood vessels at the back of the eye, we hope it will give us an indication of what’s happening to the blood vessels in the brain,” she told Scotland Tonight.

She says it’s possible that, in the future, we could get an idea of how healthy our brains are with a routine eye test.

She added: “There are now similar machines in many high-street opticians. It’s an easy way of getting some really sophisticated information about features of the blood vessels, which give you an indication of the kind of state of health which relates to – or we think relates to – what might be going on in the brain.”

Scotland Tonight is on STV and the STV Player at 8.30pm on Thursday, April 21.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country