Monkeypox has spread to 17 non-endemic countries around the world – including Scotland, which reported its first case in May.

The number of confirmed infections in England has risen beyond 500, with contact tracing currently underway to identify high-risk contacts.

As of June 15, there have been thirteen cases in Scotland, public health officials say.

The UKHSA describes the outbreak as “significant and concerning” but insisted the risk to the population overall remains low.

Professor Neil Mabbott, an expert in immunopathology at the Roslin Institute in the University of Edinburgh, explains how monkeypox spreads, the risk of getting it and what to look out for.

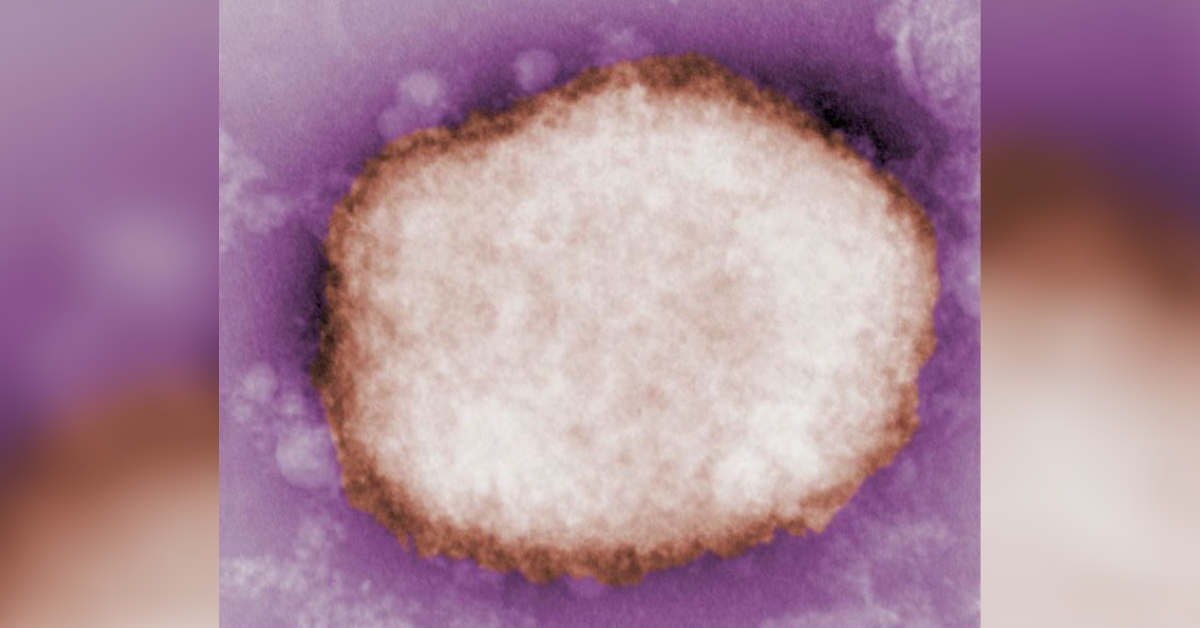

What kind of virus is monkeypox?

Monkeypox is almost nothing like Covid. Related to smallpox, it doesn’t spread or mutate as easily.

“It was originally identified in two groups of captive laboratory monkeys in 1958,” Prof Mabbott said.

“Monkeypox affects mostly species in quite removed areas of Africa and tends not to spread to humans unless they are bitten or scratched, possibly handling an infected animal while preparing bush meat.

“You have to come into close contact to get infected. When humans invade those territories, they can pass to other humans.”

What are the different strains?

There are two predominant strains of monkeypox: the West African clade and the Congo Basin clade.

“The strain circulating in the UK is West African,” Prof Mabbott explained. “I think that came from the index case, the first person who had travelled back from Nigeria. This has a fatality rate of around one per cent, whereas the Congo strain reported 10 per cent.

“Of course, those figures are based on the mostly endemic regions of Africa and would be much lower in developed health systems.”

Who is at risk?

Monkeypox can cause more serious illness in children, the elderly and the immunocompromised, including pregnant women. There have also been reports of a child in a London hospital being admitted to intensive care after contracting the virus.

Prof Mabbott said: “There’s a risk of a secondary infection meaning the virus can make [those infected] more susceptible to bacteria in some cases. The disease may be more severe in people with weak immune systems or certain risk groups.

“In the vast majority of the population, the disease is generally very mild. Some people might not know they have had it, such as in Covid. People had few symptoms while others were flattened by it.”

What chances of mutation?

There have been fears monkeypox has mutated due to the outbreaks – but it’s unlikely the virus itself will have changed.

Prof Mabbott explained that the DNA makeup of this virus ensures it spots and removes errors to successfully replicate.

“These are proof-reading mechanisms to stop them changing, as it can be detrimental to the virus – like our own cells do, just to make sure things don’t change too much.

“This virus tends not to change as quickly as other viruses like Covid, HIV or flu. They can change, but not to the same degree as we’d expect.”

CDC/ Charles D. Humphrey; Tiara Morehead; and Russell Regnery

CDC/ Charles D. Humphrey; Tiara Morehead; and Russell RegneryWhy is it spreading?

While it is harder to catch than Covid, monkeypox is still transmissible with close contact.

“We haven’t seen it spread the way it has done,” Prof Mabbott said. “Usually an index case comes somewhere like the UK and can infect household members and healthcare workers handling that patient’s bedding.

“We isolate that person and any other infected individuals and it doesn’t pass any further.

“If someone infected stayed in your house for 24 hours, that’s reasonably high contact,” he said. “It’s not like Covid in that it can travel in small aerosols over a metre or so.

“Walking past somebody probably wouldn’t be an issue for transmission. But if somebody coughed and spluttered over you within that distance, you might be at risk of transmission.”

Prof Mabbott points to lack of immunity, human behaviour and the virus “exploiting a new opportunity” to infect more people for the rising number of cases.

Can we build immunity?

“Up until 40 or 50 years ago, we vaccinated the majority of the planet against smallpox and successfully eradicated it from the planet,” Prof Mabbott explains. “Fortunately the smallpox vaccine will provide good protection against monkeypox, as they are very similar viruses.

“But the vast majority of under 40s won’t have been vaccinated except some healthcare workers. So there won’t be that residual background immunity in the community.

“That may have contributed to the efficient spread, the larger number of cases detected and it might be to do with immunity. It’s certainly contributed to a few more cases.”

Human behaviour

Prof Mabbott explains that it’s unusual to see monkeypox outbreaks in countries where it is not endemic. The virus has likely found a new way to spread at events where people are in close contact.

He said: “We only know rudimentary details of the cases for obvious reasons to protect people and avoid stigmatising groups.

“It seems the virus is exploiting an opportunity such as a super-spreader event. It has led to further onwards transmission beyond the initial close contact that you don’t usually see.

“The virus can spread through broken skin, watery surfaces and bodily fluids and droplets. As far as I’m aware, the majority of cases are men who have sex with men, that obviously requires close contact. Sexual activity will have played some role in the spread of these cases but not all.”

He added: “We live in a highly connected world where one could be in London one day and the other side of the planet the next. It’s quite easy for disease to get transmitted to other parts of the world.

“But we aren’t seeing rapid increases such as with Covid. You’d have to be very close or have direct bodily contact with an infected person to transmit.”

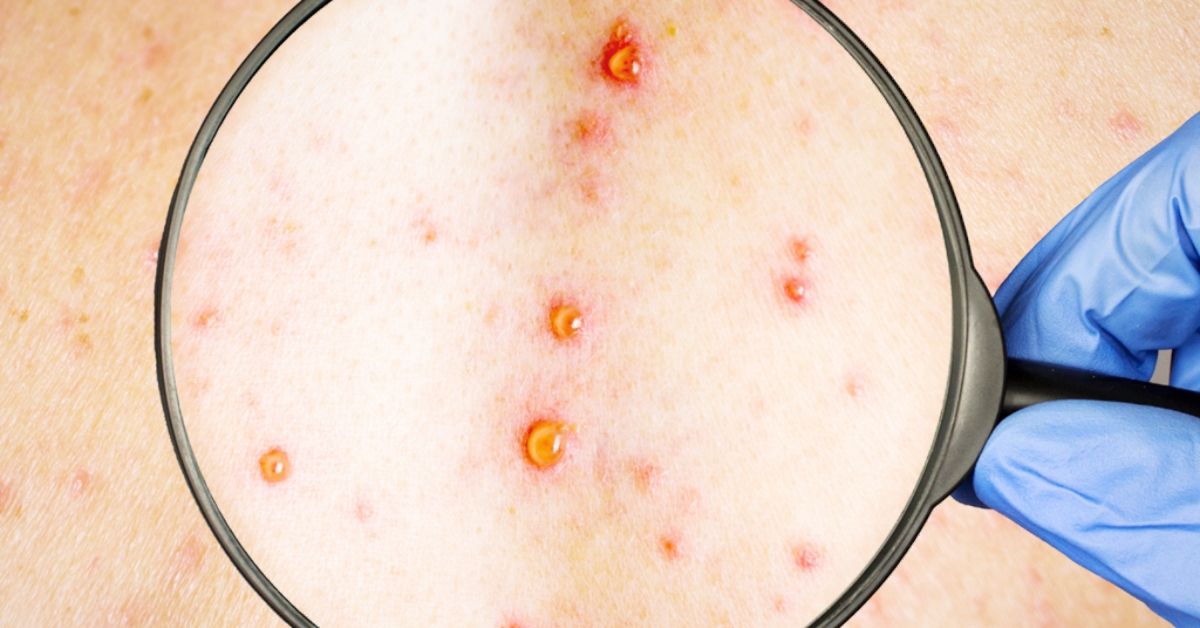

What to look out for

Initial symptoms of monkeypox include fever, headache, muscle aches, backache, swollen lymph nodes, chills and exhaustion.

A rash can develop, often beginning on the face, then spreading to other parts of the body including the genitals.

The rash changes and goes through different stages – it can look like chickenpox or syphilis, before finally forming a scab which later falls off.

“The key thing is, if you have been exposed to someone with the virus and develop a strange rash, immediately contact the NHS. That way you can be risk assessed. and you’ll be told to isolate if required,” Prof Mabbott said.

“Three weeks is the recognised incubation period. This is how we can control the spread. Like chickenpox, which is a more regular disease, once it starts to scab off, you’re no longer infected.”

He added: “The health authorities have increased surveillance to identify cases and close contacts. Vaccination may also be given to those who have either been infected or are at high risk of contact. Ideally, like covid, as early as possible or preferably before.

“If we do this by monitoring infected and identifying close contacts, it would allow this outbreak to burn itself out.”

The smallpox vaccine

A smallpox vaccine is being used to immunise those infected and close contacts of cases and is reported to be around 85% effective in preventing the virus.

Prof Mabbott explains: “We don’t use the original smallpox vaccines anymore because they were live vaccines and couldn’t be used in highly immunocompromised individuals. That was originally based on smallpox itself. It could cause quite serious issues.

“Imvanex is a third generation vaccine which is designed to be treated so it can’t replicate in the body, amplify and cause disease. It trains our immune system to react to smallpox and it doesn’t have the safety issues. It’s not without side effects, but it’s the effects typical of a vaccine, such as the pain at the site of injection.”

How is the picture looking for the UK?

Prof Mabbott predicts more cases will be confirmed but that the outbreak should eventually wane as authorities monitor cases and close contacts.

“Identifying and locking down contacts should mean this outbreak should reasonably burn itself out,” he said.

“I don’t see measures such as travel bans happening. I can only speculate but for the vast majority the risk is incredibly small.”

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country

PHS

PHS