The lives of at least five professional footballers struggling with their mental health have been saved during the pandemic, according to a charity.

BackOnSide said the Scotland-based players required urgent support as they struggled to cope with various issues.

“I don’t know what would have happened if we weren’t here,” the charity’s Libby Emerson told Scotland Tonight for a special programme examining mental health in football.

Young boys and girls dream of becoming footballers, of playing in cup finals at Hampden and one day pulling on the dark blue of Scotland.

But for the few who make it to the top of the sport, there are thousands of promising hopefuls left behind – so what happens to them?

What about the players who lose their careers to injury, or those who try to play in silence through mental health problems?

Scotland Tonight spoke to those who’ve experienced the darker side of football and asked what’s being done to tackle the stigma associated to mental health issues in the sport.

‘One day, your dream ends… it’s finished’

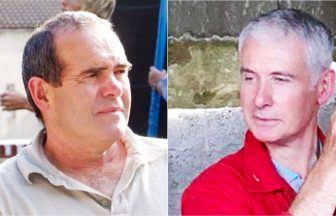

Five years ago, Chris Mitchell died from suicide, just a few months after his dream football career was cut short by injury at the age of just 27.

Chris came through the youth system at Falkirk and played for Scotland Under 21s and clubs including Bradford City and Queen of the South before leaving Clyde in January 2016.

“One day, you’re living your dream and the next day, you’re not. You’re out the door and the structure of your life – getting up, going to training doing all that – is finished within 24 hours,” his dad Phillip says.

“He liked to be around people – he was a very sociable individual, the first in the dressing room in the morning and the last to leave.

“He loved the camaraderie, the dressing room and everything that went on. He used to come back and tell us stories and it was great – he loved it.”

SNS Group

SNS GroupAs his injuries began to mount up, Chris struggled to cope with spending more time on the treatment table than the training pitch.

“The fit ones go out [the dressing room] and turn right on the pitch. The other ones turn left and you’re marginalised, you think you’re maybe not part of the whole body of the team and these things started to get Chris down.

“But, at the same time, you want to play football and it’s your livelihood – so you want to keep all these secrets to yourself.”

In the wake of his death, Chris’ family launched the Chris Mitchell Foundation – an organisation that supports those struggling and trains club staff to spot the warning signs around mental health.

“Lots of people came down to the house [after Chris died] and you’re sitting there thinking, ‘what’s happened here?’,” says Phillip.

“From retiring in January, he’s dead in May. What is in football to help players? We were asking the players in the house and they said ‘we don’t know’ or ‘there is nothing there’.

“If they have concerns a person is not alright, they need to have the confidence to approach that person and ask the question, so we’re not relying on that person who’s suffering to take that step.”

‘I’ve been pushed out’

David Cox always knew he wanted to be a professional footballer and has spent years doing what he loves across the Scottish leagues.

The 32-year-old made headlines last week when he announced his retirement after allegedly receiving abuse from a fellow player about an attempt to end his own life.

Albion Rovers forward David is all too aware of the game’s darker side.

“Growing up chasing every young boy’s dream to be a footballer was amazing,” he says. “When you start getting involved with professional clubs, you feel you’re kind of doing what every person your age wants to do.

SNS Group

SNS Group“You play football when you’re younger because you enjoy it. But as you leave school and you’re getting paid, you’re then fighting for a contract every year and there’s a lot more pressure.

“If you’re not performing well, if you’re not making the team every week, if you pick up injuries, these will all factor into what happens to you at the end of the season.”

Seven years ago, David spoke publicly about his mental health battles and suicide attempts.

Since then, he has endured horrific abuse on and off the pitch.

“I heard a few things from the stand after I told my story,” he says. “I remember one of the shouts was ‘do it properly this time’.

“I’m no angel on the park and I’ll get stuck into boys and we say things, but when it comes to personal stuff there needs to be a line.”

David feels support has not always been there from clubs, and he fears other players are suffering in silence to avoid generating a reaction.

“Some clubs have been absolutely amazing with me, really really good,” he says. “Club chaplains take the time out to speak to you; club directors, chairmen, managers do whatever they can help you out.

“I’ve also been at clubs where I’ve been pushed out because of my mental health.

“If somebody feels like they want to come out and speak, it’s going to be in the back of their mind that it will affect their life in football.

“Unfortunately there are always going to be managers, clubs or staff who look at that as a problem.”

‘Five players might have ended their lives’

“The abuse players get if they talk about their mental health is wrong and it needs to change,” says Libby Emerson from mental health charity BackOnSide.

Her charity has helped at least five players in Scotland’s professional leagues from “ending their lives” over the past year and she thinks clubs need to do more and accept the help that’s available.

“It’s hard to get into clubs, I’m not going to lie,” she says.

“A lot of clubs don’t realise there’s a mental health issue going on. But the problem is, they’ve all got mental health, we’ve all got mental health, just like we’ve all got physical health.

“If a player broke his leg on a pitch, they’d get support in an instant, the best of support and doctors to look after them.

“But when someone says their head’s a bit broken, it’s just ignored.”

Libby believes perceptions of footballers all being well paid and living luxurious lifestyles causes a problem.

“The general public will look at them and think they’ve got everything,” she says. “They’ve got the big house, the nice wife, the fancy cars, the houses abroad – why should they be upset and depressed?

“Everybody struggles, it doesn’t matter what money you’ve got, what money you’ve not got, or what lifestyle you got.”

‘Football has work to do’

Motherwell Football Club has been touched by the tragedy of suicide, both among its playing squad and its support.

Chief executive Allan Burrows believes football as a whole is getting better at dealing with mental health, but acknowledges there’s more work to do.

“We see it as our obligation to get involved in these really hard-to-reach taboo subjects,” he says.

“Unfortunately, and sadly, we as a football club have been scarred with it [suicide] as well. So it’s a subject that’s been really close to our heart. It’s been really painful for us and we feel that it is our duty, our obligation to try and shine a torch on it.”

The club has developed a focus on life after football – helping to ensure players don’t leave without a plan B.

SNS Group

SNS Group“I think we’ve made improvements, but we’ve got a lot of work still to do,” Allan says.

“We need to continue to talk about it and raise it as an issue. It needs to constantly be the message; you need to constantly push it all the time.

“We will continue to do that as a club. I hope other clubs will continue to do so as well and other sports and other outlets will continue to do it.

“And if we all do that, and we all try and take it more seriously, then hopefully we can stop this other pandemic that is going on in Scotland at the moment.”

Mental health helplines

- BackOnSide: 07528 243 100

- Samaritans: 116 123

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country