Daniel Watson feels at home in the Swedish city of Uppsala, about 45 miles north of Stockholm.

Originally from Clydebank, he moved to the Scandinavian country for university and has now started a family.

And one of the biggest perks of his new life is the fact he pays just £630 a month for rent-controlled flat, which includes his heating, hot water and other bills with the exception of electricity.

“I have a ‘ungdomslägenhet’, which is like a youth apartment,” he told STV News.

“That means you have to be under 27 when you apply for it, which made it easier to get somewhere central with a garden.

STV News

STV News“There’s no deposit on the flat. I didn’t need to give rent in advance. If you’re having a family (in Scotland) you’re going to worry about your bills every month. Here, there’s just that stability.

“I’ve no boiler. I don’t need to put on the heating. The heating is on 24/7 in the winter and is always at the same temperature. I can’t imagine worrying about my boiler breaking down in the middle of a Glasgow winter.

“That’s the big difference, back home in Scotland they don’t understand that we’re a northern country. We shouldn’t build houses like it’s for London. We should build houses for our own needs with good insulation and heating.

“That’s what they’ve done here. I hope they can be a model for Scotland.”

At a ceilidh in central Stockholm, the Scottish community are among those navigating the twists and turns of the country’s rental system.

Janet Cormack, from Edinburgh, now lives in the heart of the city but says it has been difficult to find accommodation.

She told STV News: “There’s a lot more rules in place about how it’s organised, very long waiting lists, but when you do get a place, it’s very high quality.

Andrew Montgomery, from East Kilbride, added: “There’s the city municipal market but you’ve got to have been in the queue for years and years, so if you come over and you’re on your own you’re at the mercy of second-hand letting.”

Tough rental market is fraught with problems

Sweden has had rent caps in place in large towns and cities for decades.

Prime properties can be rented for £600, but it’s fraught with problems – ten-year waiting lists and a black market for leases are common, so managing the twists and turns of the rental market is tough.

One of the big issues in cities like Stockholm is that there aren’t enough rent-controlled homes available.

STV News

STV NewsIt forces many out of the city and into the suburbs. As a result, there’s a big illegal subletting culture, with some people desperate enough to offer bribes to get a flat in a desirable area.

The first step for many people to get a rent-controlled home is to join a digital queue.

The longer you’re in the queue the more points or credits you build up. Many do this when they turn 18 but the waiting list is anywhere from ten to 20 years long.

Among those with experience of the queue is Lena Johansson, who managed to secure a one-bed flat in a wealthy Stockholm suburb.

Her rent is £615, but it goes up every year. This year, it’s by 5.3%, but she can’t challenge the increase.

She said: “We can’t challenge it because if you don’t want to pay your rent, there will be some other tenant who will.

“The rental market in Stockholm is hard. I mean, Stockholm is a popular city, it’s the capital, a lot of people want to live here.

“Ten years before you get somewhere to live, that’s crazy. I can remember my parents when they were young – they walked down to the office and said, ‘Do you have a bigger apartment?’ and were told, ‘Yeah, you can have it’.

“That sounds like a fantasy to me when I hear my parents say that. Now, it’s harder, and people will be in the queue for a long time or perhaps illegal sublets, second-hand, third-hand, obviously illegal, but it’s a desperate situation for some to find somewhere to live.”

STV News

STV NewsThe tenants’ union is very powerful in Sweden. They negotiate rates with landlords that are often set in the tenants’ favour.

The strength of the rent cap is problematic for those in the housing industry.

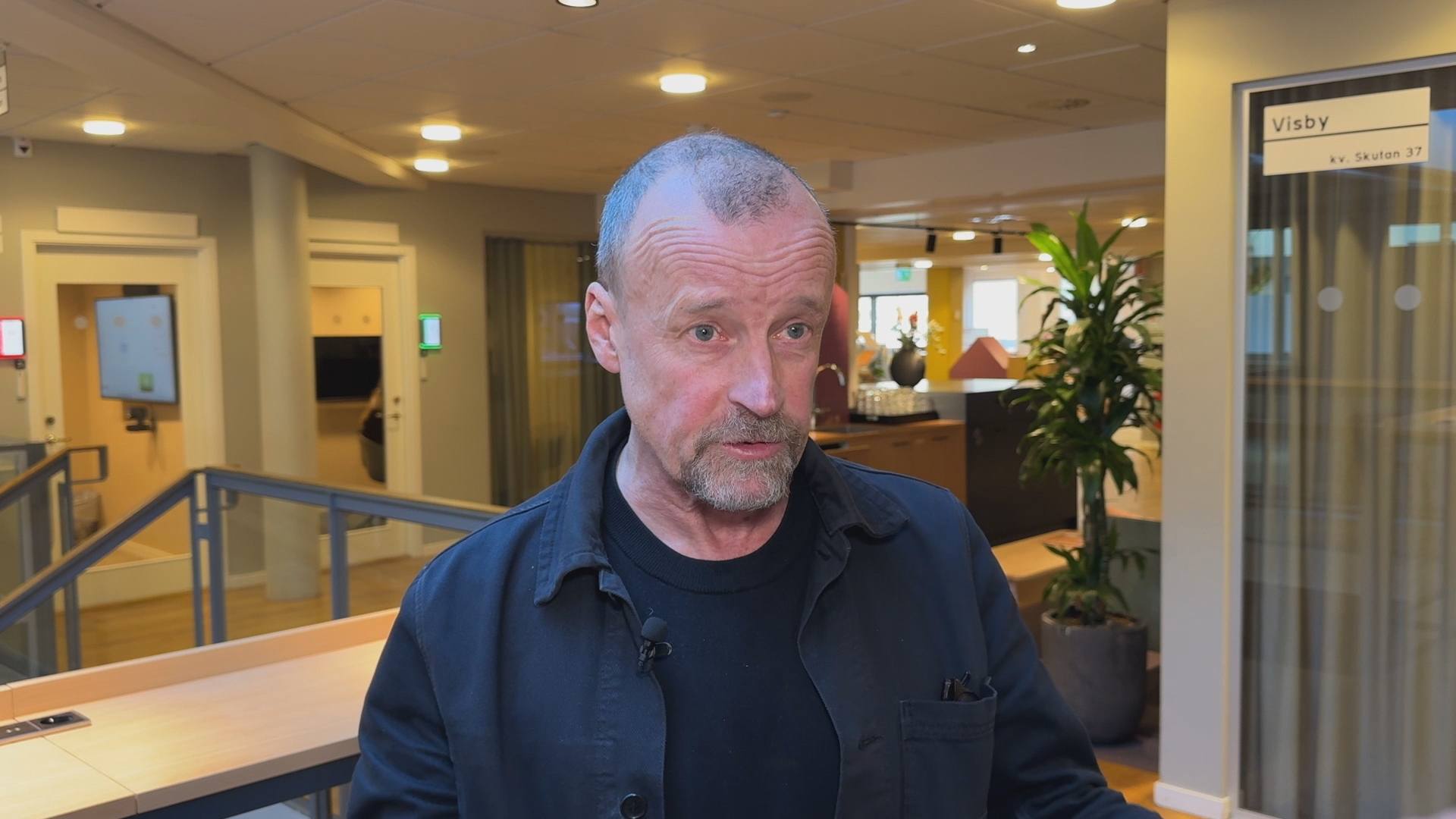

Tomas Ernhagen, chief economist at the Property Federation of Sweden, said: “When these levels were set, we were back in the 70s, so you have to change the values to a modern way of thinking.

STV News

STV News“But you can’t because you’re forced into the world of the 70s. It may have been a nice world but it’s a problem for people moving in and out of apartments in Stockholm. That’s why we have decade-long queues – they’re perceived as cheap living for what you get.

“We have a thriving black market as well. The main problem for the rental market is ‘what can they do?’

“They have something that is very valuable, but they are not getting the direct income from managing those apartments.

“It’s very low. What can they do? They can sell it, so it goes to a condominium.”

Nearly 90% of all apartments in Sweden were available for rent in the 70s. Today, that figure is 30%.

STV News

STV NewsBut Mr Ernhagen has a message for the Scottish Government about introducing rent caps – don’t do it.

“If you look at the economic school book, don’t do it because you get a shortage,” he said. “If you have a quite flexible system, keep it, look to provide for people who have less resources to fix the situation.

“They need to be helped but don’t mingle with how the market functions, because you’ll build less than you should and you’ll get other problems. In Sweden we don’t provide well for those who are having tough times.

“We are building less per capita, there are worse problems with homelessness, and (a decline in) how proudly we live. These three problems are explanation enough not to do this in Scotland.”

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country