Psychiatrists say there is not enough evidence to draw a direct link between a sharp increase in young people being prescribed antidepressants and mental health waiting times.

Public Health Scotland figures show that medication was prescribed to 20,825 children aged up to 19 in 2019-20.

That is an increase of more than 80% in less than a decade (11,507 in 2010-11).

However, in that time it has almost trebled among ten to 14-year-olds (541 to 1501).

And it has almost doubled among those aged 15 to 19 (10,877 to 19,190).

STV News

STV NewsDr Jane Morris, vice-chair of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland, said: “We would have to have a lot more careful research done to see whether the apparent association is causative.

“I think that’s something that all of us in Scotland are calling for at the moment, which is an improvement not only in the amount of research that is undertaken with young people, but also I think people are waking up to the need for good public health figures.”

Guidelines say antidepressants should only be offered to a child or young person in combination with psychological therapy.

Dr Morris added: “We wouldn’t oblige someone to take a talking therapy if they were unable to or they felt strongly they didn’t want it, but certainly we do follow those guidelines.

“Young people are not prescribed medication as the first option for treatment, and if they are, then the preparation for treatment, the screening for physical conditions and other vulnerabilities, the attempt to make sure it is embedded if not in a talking therapy at least in very regular monitoring and review would convince you that it’s far from being a shortcut.”

Antidepressants can be prescribed to children and young people under certain circumstances for a range of conditions such as depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

However, they will only be offered medication after seeing a specialist.

The Covid pandemic has put increased demand on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services in Scotland (CAMHS).

At the end of September last year almost 2000 (1978) children and young people had been waiting more than a year for treatment from specialist child and mental health services.

That is more than double from the previous year (959).

Between July and September, only 78% were seen within the Scottish Government’s waiting time target of 18 weeks from referral to treatment.

‘It made me more suicidal. It made me really struggle which I didn’t realise at the time.’

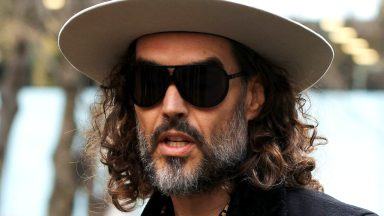

Stephanie Craig

After attempting suicide at the age of 14, it took a year before Stephanie Craig received help and was prescribed antidepressants.

She said: “It made me more suicidal. It made me really struggle which I didn’t realise at the time.

“I just thought it was the trauma and blamed it on all that, but it was a rapid decrease in my mental health as soon as I got put on it.

“I didn’t want to be alive. I felt everything was against me.

“My head was just so messy because of this medication.

“Some of my friends are on antidepressants and they live amazing lives, and it really does help them so I believe they do work, but not without support and not without another talking therapy or another person there to talk to.”

‘We thought that they knew what they were doing.’

Mark Smith

Joshi Smith’s parents noticed she was experiencing bouts of anxiety and depression when she was ten-years-old.

Her father Mark said: “The first thing they did was prescribe her antidepressant at 12.

“Fluoxetine was the first drug that they put her on. She was against this because she didn’t like what they did to her. She said herself that they took her spark away.

“As soon as she showed some kind of objection to this, they kept changing the drugs and put her on other antidepressants and we trusted them.

“We had no idea. We thought that they knew what they were doing.

“There is no magic pill. That’s a band aid covering a wound. That’s not solving anything. And there is no solution. These things offer no solution.

“We worked our way up through various levels of psychiatry at the place there until we got to the head psychiatrist who literally threw his arms in the air and said ‘we have nothing left in our armoury for her’.

“And she was there, and I don’t know what they thought would happen when they said that.

“But that must have been devastating for Joshi to say there’s no help available.

“So, at that point, not long after that, she began self-medicating and one thing led to another and you know, she became out of control.”

Unfortunately Joshi did not get the help she needed to get better and died of an accidental overdose while attempting to self-medicate.

Joshi’s parents feel a lack of effective treatment for their daughter led to her tragic death.

They are now campaigning for a more compassionate and flexible system of mental health treatment in Scotland.

The Scottish Government says it has invested £40m to improve child mental health services and to clear waiting lists by March next year.

It is also working with health boards to ensure targets are met, and have provided extra funds for alternative treatments within communities.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country