Today’s judgement was unanimous and unambiguous. Holyrood cannot legislate for a second independence referendum unless it is done with the agreement of the Westminster parliament.

Two issues were before the court.

First, could they consider a reference by the Lord Advocate, the Scottish Government’s chief legal officer, to clarify the issue? And, secondly, if they accepted that the reference is legally competent, could they rule on the legality of a referendum bill about to be considered by MSPs?

In essence, they decided that they could consider the reference sought by the Lord Advocate and, having considered it, unanimously concluded Holyrood does not have the legal authority to stage a plebiscite without Westminster’s consent.

STV News

STV NewsAt the hearing into the issue, it was accepted by both sides that as a matter of law, any bill that sought to change the constitution of the UK was unlawful.

The Lord Advocate argued that as a referendum was consultative it had no legal affect and consequently could not of itself change the constitution. The proposed referendum bill was therefore within the scope of the powers of the Scottish Parliament.

That argument has been unanimously rejected by the court on the ground that the proposed bill relates to a reserved issue (the constitution of the UK).

In addition, the court said that, as a matter of law, it was entitled to consider the purpose and effect of any legislation.

The effect of a referendum bill is to bring about a change in the union between Scotland and England, and is therefore outwith the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament.

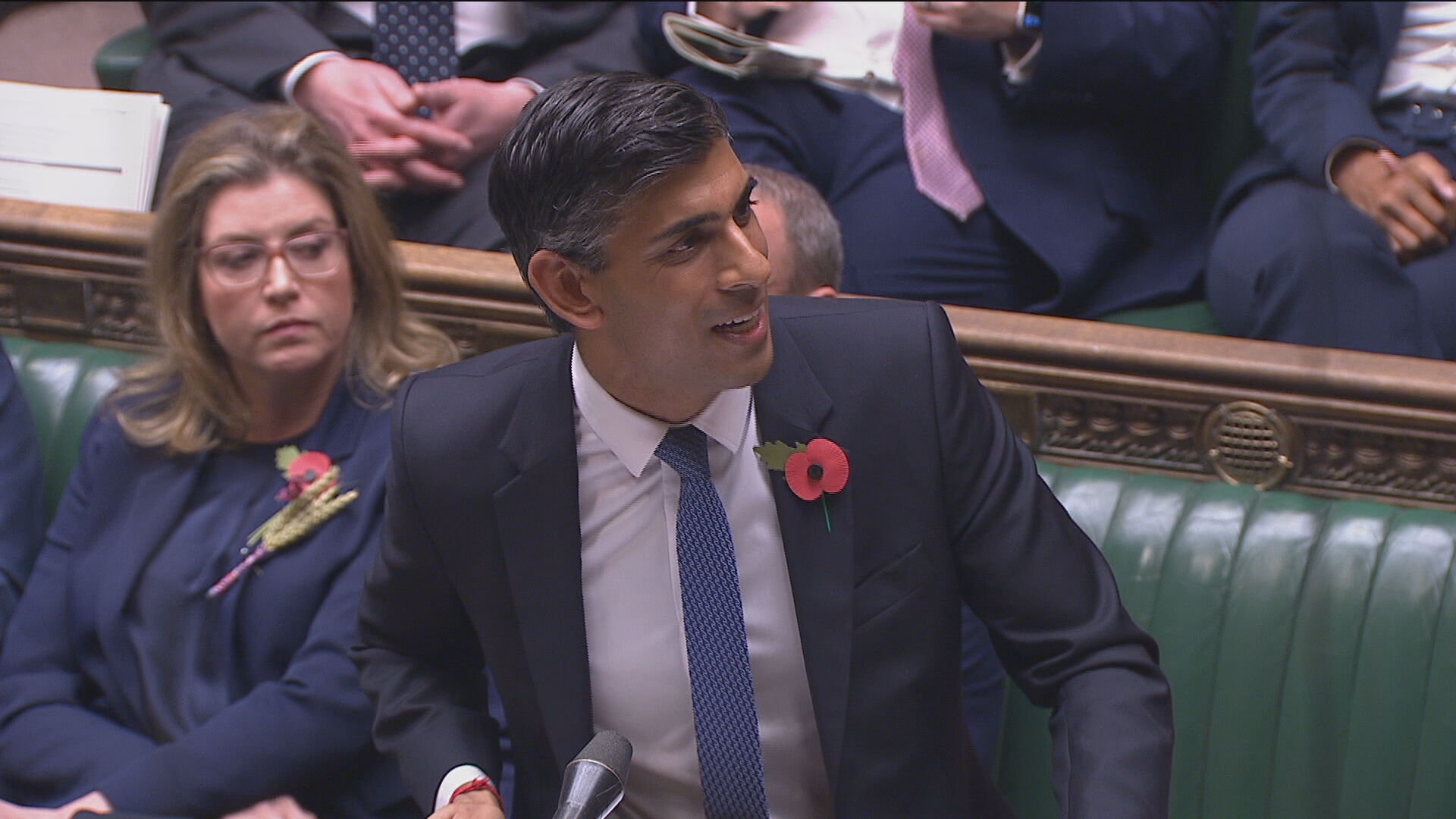

Supreme Court judge Lord Reed made the point that in 2014, the Westminster parliament, by means of an order in council, delegated authority to Holyrood to stage such a plebiscite.

Supreme Court

Supreme CourtNo such agreement to hold a second referendum exists and, in the absence of that agreement MSPs have no power to unilaterally stage a second vote.

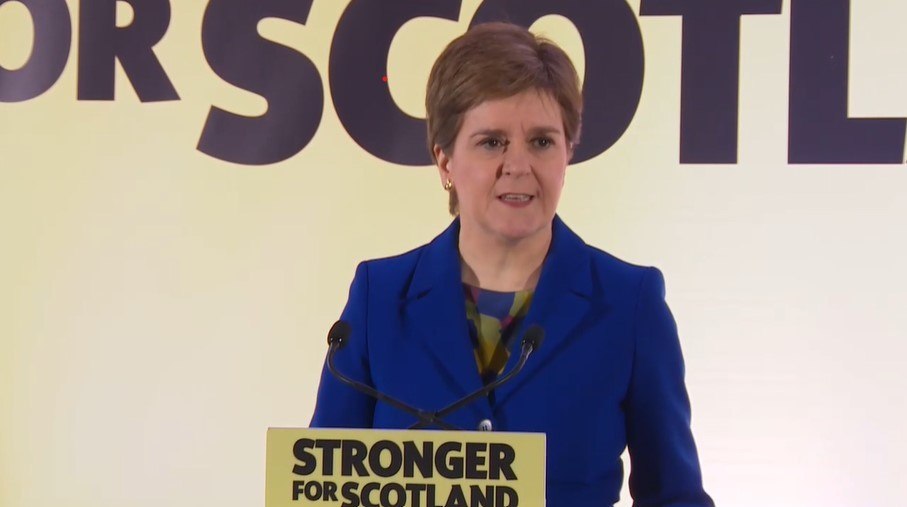

The First Minister was quick with her response, arguing that the ruling demonstrated that the union was not a partnership of equals if Holyrood could not stage such a vote.

That, of course, is a political argument, but it does raise a wider issue. Is the Scotland Act fit for purpose?

The 1998 Act was designed to cement devolution, not provide a springboard to independence.

Those supporting independence will argue the 1998 Act imprisons Holyrood on the key issue of self-determination and as such should be amended.

Unionists will point out a mechanism for holding another vote exists, but it requires the consent of both parliaments.

Although the staging of another vote would require a bilateral agreement, what is clear, and has been reinforced today, is that Westminster has an effective veto over any independence referendum.

The political consequence of the ruling is that the Scottish Government will now seek to turn the next general election into a de-facto poll on independence.

That strategy is high risk. The cost-of-living crisis is likely to dominate the next election.

To what extent can the independence issue cut through that? Indeed, if support for pro-independence parties falls short of 50% of the voters, won’t the issue then be buried by their very own strategy?

STV News

STV NewsThe fallout from today is likely to be dominated less by the arguments around independence, but around the argument about the right to hold another poll.

This judgement came quickly for two reasons. First, the judges were unanimous, and secondly, the legal issue was pretty clear cut.

Holding a referendum is a matter of law. The politics of the issue will now intensify around the central issue of the right to self-determination.

Today crystallised once and for all that Holyrood has no power to stage a referendum on a matter reserved to the UK parliament.

But the politics of this is about to get a whole lot nosier.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country

iStock

iStock