The new SNP-Green cooperation agreement looks set to entrench a degree of stability to the government as Nicola Sturgeon forges a new partnership aimed at delivering shared goals and paving the way for a second independence referendum within five years.

As a model of cooperation, it stands uniquely in the history of cross-party agreements in recent times. When first mooted, I remember thinking, ‘why does the First Minister want this?’.

On the central constitutional question of this parliament, the Scottish Greens could be relied on to help facilitate another referendum and the custom and practice of recalibrating the budget to meet Green policy priorities probably would have given the stability desired.

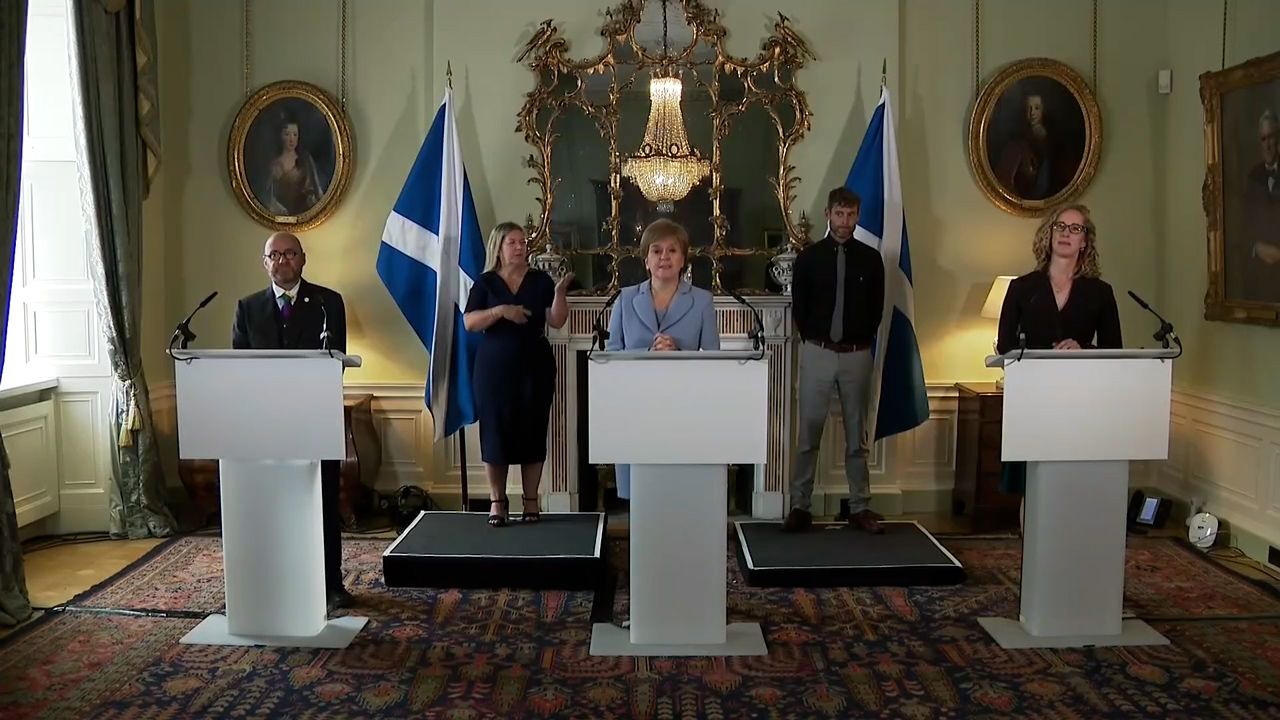

Instead, the Greens have been brought into government, being rewarded with two junior ministerial posts as part of an agreement which goes well beyond the scope of a confidence and supply arrangement, but stops short of a full formal coalition.

A coalition would have involved whipped votes on all legislation and Patrick Harvie and Lorna Slater would have been expected to be bound by collective responsibility on all aspects of policy.

For the Greens, it looks like a ‘have your cake and eat it’ arrangement, a chance to establish the notion that they can help govern the country whilst simultaneously being on the inside without surrendering their distinctiveness.

The key issue for any junior partner is being able to demonstrate that you can make a difference, that you are more than voting fodder and that you can help broaden your appeal by showing responsibility in the administration of the nation’s affairs.

What does history tell us?

The Lib-Lab pact of 1977 kept the Labour government in office and kept Margaret Thatcher at bay for another two years. Ultimately, it was of considerable use to Prime Minister James Callaghan, but frankly did little or nothing for the Liberals, who failed to march to the sound of gunfire – to quote Jo Grimond -at the 1979 general election.

After the creation of the Scottish Parliament, Labour formed coalition governments with the Liberal Democrats in 1999 and 2003. Critically, the Lib Dems were able to point to concrete achievements, such as voting reform for councils, as evidence they made a difference.

STV News

STV NewsThe Scottish experience worked because the two parties had a certain ideological simpatico on issues such as constitutional change and social justice. Where, however, historical anchors point to radically different traditions, the coalition model can become unstuck.

When the Tories and Lib Dems entered a coalition in 2010, it had disastrous consequences for the Lib Dems, who were electorally garrotted for what was seen as a betrayal of basic values.

The tremors of that time still define the party’s marginal status today. The Scottish Liberal Democrats, once a partner in government, are now totally irrelevant when it comes to forming an administration at Holyrood, and all because of a miscalculation on doing a deal with the Tories.

Trouble ahead?

It begs a question – are there lessons here for the Scottish Greens? It must be a concern that voters might see them as no more than an adjunct to the SNP and that they fail to point to concrete achievements which could not have been delivered through a confidence-and-supply arrangement.

More worrying, if support for the SNP falls materially, will the Greens suffer a similar fate? This is not a risk-free arrangement.

When Holyrood was established, it was hoped that cooperative politics would be the order of the day and seeking consensus on policy would drive all parties. That hasn’t happened because the lofty ideals of the parliament’s creators have been torpedoed by the essentially tribal nature of politics. It was, I suggest, always going to play out that way.

For the Greens, this is a new phase in their development as a mainstream party. They hope they will not be buffeted by changing electoral trends. On road building, North Sea decommissioning and a whole host of issues, there looks to be scope for trouble ahead.

They must demonstrate that they can benchmark their principles against policy, otherwise in the future they may well ask if the cooperation agreement was to prove the price of their soul.

Flickr

Flickr