Last year the Scottish Parliament turned 20. In those two decades the near uniformity in some key policy areas of the pre-devolved era bit the dust as a new settlement helped fashion a different end game.

Whether it be free tuition or free personal and nursing care, Scotland diverged from England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

This is how the architects wanted it to be and the lack of looking over the shoulder to see what was happening elsewhere was a sign of a new institution which did not operate in fear of ridicule for doing things differently.

Politicians at Holyrood like to collectively own what they see as the successes of the institution. They should also own the failures too. Nowhere is that more evident than in the shocking statistics for drug-related deaths.

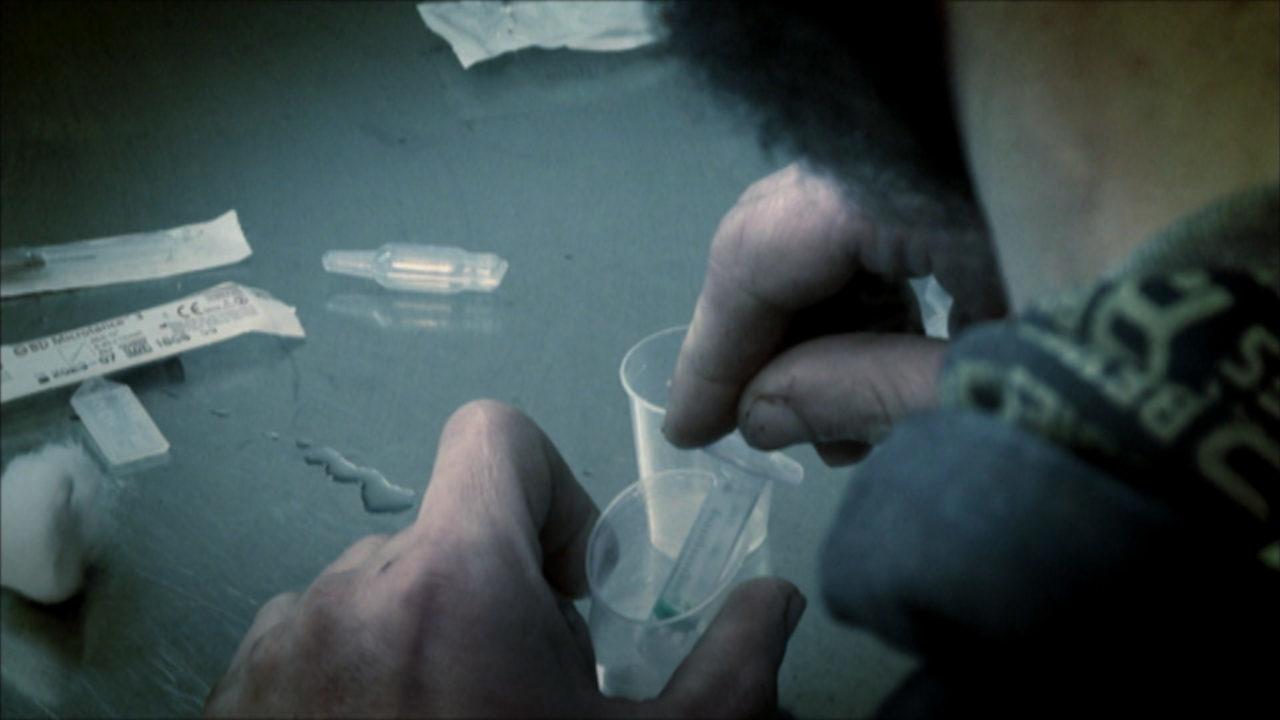

When the Scottish Parliament assumed full legislative authority in 1999, there were 291 drug related deaths in Scotland. A decade into the New Jerusalem and that figure stood at 545. Last year, when it was a case of happy 20th birthday Holyrood, the figure rocketed to 1187.

Put another way, there has been a 400% increase in deaths. Scotland, with a population of five and a half million reports a similar number of overdose deaths as Germany with a population of 83 million.

The head of the Scottish Drug Deaths Taskforce (SDDTF), Professor Catriona Matheson, says people are being “neglected” and “ignored”. Her organisation says many of these deaths are avoidable tragedies.

That Taskforce was established in 2019, the latest effort in a long line of initiatives designed to win what the tabloids used to refer to as the ‘war on drugs’. It’s not a fashionable headline anymore since the war was lost long ago.

In three decades of reporting, I have covered every twist of the ‘bigger picture’. Back in the day, when cheap heroin took hold in the 1980s, harm reductionists joined battle with those who took a hard-line on abstinence or ‘just say no’.

Then there was the debate about the use of methadone. Then the endless status quo v decriminalisation v legalising debate, one politicians loved to dance around or skip altogether since it risked offending the sensibilities of people who had never been touched by the horror.

Their conservatism also spoke to a parental anxiety, people who harboured fears that legalising more drugs would be a slippery-slope to ‘turn on, tune in, drop out’ as Mr Timothy Leary used to invite in the 1960s.

It seemed compulsory for politicians to be ‘tough’ on drugs in the belief that somehow threatening everyone with the full might of the law would induce a fear in those who sold them and would change the behaviour of those who were increasingly lost to them. The near biblical injunctions no doubt made Ministers feel better even if their hollering fell on deaf ears.

The nadir in PR was the sight of a cross-party group of politicians wearing baseball caps back to front in an effort to look cool whilst delivering their anti-drugs messages.

There was a general consensus that to see addicts as criminals was to miss the point and would merely inflate the cost to the public purse by the endless pursuit of the vulnerable through the criminal justice system.

Not to be outdone in this pointless public relations frenzy, the police would laud the triumph of historical drug hauls aimed at cutting off supply whilst all of the time the deaths increased. It was good copy for the force but couldn’t mask what officers knew, it wasn’t of itself anywhere near enough.

What is to be done?

Part of the answer has to lie in dealing with another of Holyrood’s failures and one that should truly shame. The deeply entrenched, inter-generational poverty buttressed by unemployment and poor housing is a recruiting sergeant for the drugs trade.

Drug use is 17 times higher in Scotland’s poorest areas compared to the wealthiest. Dundee, Glasgow and Inverclyde swell the statistics which are a story of lost lives whilst East Renfrewshire and East Dunbartonshire are enviously near the bottom of the tables.

Breaking the cycle of poverty-exclusion-addiction-death-repeat, is not easy and to be fair to all of those who have been in government they have all debated this long and hard.

Perhaps approaches in the past have over-relied on one philosophical starting point when in reality every single person with a problem needs a solution tailored to their individual needs.

That’s why it simply isn’t good enough that only 40% of people who need treatment are estimated to be receiving it, according to the SDDTF.

Those who started on heroin in the 1980s are dying after decades of use in which lives might have been stabilised – whatever that means – but have not been turned around.

The litmus test for a socially-just society is how it deals with the poorest, the most excluded. This issue is not one of the political mainstream but it should be.

The figures, appalling as they are, might be small in relation to the overall population but a lot of these deaths can be avoided.

I can only imagine the sheer frustration of every GP, every healthcare professional, every counsellor who has tried to make a difference only to see hard work and professionalism defeated by death.

Actually, I will take that back. I can’t imagine it since I have never met anyone who has died of a drugs overdose. And therein lies part of the problem. Issues scream loudest when they have the weight of numbers which threaten a popular dissent.

The stats will change again on Tuesday when the number of deaths in the last year are published. They are likely to set another record. Journalists will canvass the opinions from the usual community of interested ‘stakeholders’.

If good intentions counted this would have been reversed long ago. I can only hope that this time next year there are signs that fewer deaths is the start of a trend that careers downwards. However, never was the phrase ‘more in hope than expectation’ more apt or more depressing.

STV News

STV News