Stuart Macgee dreamed of a career in the RAF after university, but before he could finish his studies he was diagnosed with epilepsy.

It turned his whole life upside down and rocked his confidence.

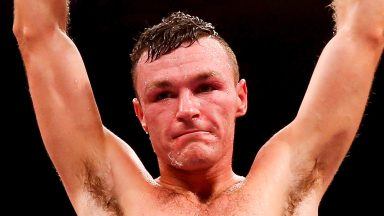

Stuart, from Ayr, can now manage his condition – he can sense when he’s about to suffer a seizure – but he knows that many of the other 60,000 epileptic Scots are struggling to cope.

He spoke to STV News as a new study revealed that more than three-quarters (76%) of all epilepsy-related deaths in Scotland could have been prevented.

The first study of its kind by Edinburgh University found that a lack of specialist support and treatment services was leading to unnecessary, premature deaths.

“I was shocked [when I was diagnosed], I had all these questions,” Stuart, 44, said. “I started on medication but it made no change.

“Job wise… what do you do? What if I’m having seizures, will people be laughing at you, what will they say? How did I tell my friends? It’s nothing to be ashamed of, but at the time it was a big thing. I think my mum felt helpless.

“The big question was ‘how do I live my life with epilepsy?’. I’m no longer fully in control of my own body. There was always nerves when friends asked if I was going to football or golf. I’d say I couldn’t make it and was always making excuses. I didn’t want people to see me.

“Initially, the only people who knew were my family. It took a long time before I was honest with people and told them I had epilepsy.”

Stuart now has a seizure every two weeks or so and can feel them coming on, but in the past he has hurt himself during episodes.

“I used to get a warning sensation, but one time I wasn’t feeling anything and decided to iron a shirt,” he recalled. “My hand was white across the fingers and I thought ‘I’ve burnt my fingers on the iron’. I’d had a seizure and had to be sent to the burns unit in Glasgow.”

Although he admits it’s still challenging on a daily basis, regular access to an Epilepsy Specialist Nurse (ESN) and advice from Epilepsy Scotland has been pivotal in helping him live well with the condition.

His family has also provided great support, but Stuart counts himself lucky and worries for those newly diagnosed who can’t access or aren’t aware of specialist services.

“I don’t criticise the doctors or nurses because their hands are full, they have so many patients,” he said. “We could do with so many more specialist nurses. Not everyone can get to their appointments. There’s people out there who don’t have friends, family support, and it’s really difficult. There is help out there.”

‘We woke up and she was no longer there’

Philip Bergqvist’s sister Juliet was diagnosed with epilepsy when she was 14 and, for most of her adult life, was able to control her seizures.

But in her 40s, the condition caused her mental health to suffer. “Things got very bad,” said Philip “The help was difficult to come by unless you had a supportive family. But there was no cure, and sadly it all got too much for her, and in 2016 she took her own life.

STV News

STV News“It came out of the blue, which is always a worry for families. She always promised she would never take her own life. But one day we woke up and she was no longer here.”

Juliet’s family have since set up a memorial fund in her name and part-funded the new study in conjunction with Edinburgh University.

“We really need to overhaul the way we deliver epilepsy care,” said Dr Susan Duncan, a lead on the study and senior lecturer at the Muir Maxwell Epilepsy Centre.

“One of the most striking things is that of 1921 people who died, 62% of them attended A&E with a seizure-related episode and only 27% got to see a neurologist.

“This study was done before Covid-19 and I suspect if we did it now, we might find it is even worse. One of the most troubling aspects during Covid was that epilepsy nurses were put to general work.”

‘Postcode lottery’

Academics and charities recognise the need for more specialist nurses across Scotland and argue that the level of care and its accessibility depends on geography.

Some health boards, such as NHS Borders, don’t employ ESNs for adults, while in NHS Ayrshire and Arran, there can be a 68-week wait to see neurologist – meanwhile, it’s just 11 weeks in NHS Forth Valley.

A Scottish Government spokesperson said: “We are aware of this new report and will consider its important findings as we continue to ensure that all people living in Scotland with epilepsy are able to access the best possible care and support.

“We are investing £4.5m over five years to implement our Neurological Care and Support – National Framework for Action, to ensure everyone with a neurological condition, such as epilepsy, can access the care and support they need to live well, on their own terms.”