When death visits there is a natural human instinct to veer towards seeing only good in the recently departed. When the deceased is a public figure observations can be overly respectful. When that person is much admired, tributes can become a conductor for the conferring of sainthood.

When Scotland’s first-ever First Minister Donald Dewar died on October 11, 2000, tribute programmes declared him the Father of the Nation and the Robert Burns song ‘A Man’s a Man for A’ That’, was played incessantly. I remember having a chuckle as I thought, ‘he would hate every minute of this’.

There was also some behind-the-scenes wrangling over the use of Glasgow Cathedral for his funeral. This confirmed agnostic would have hated that too. In fact, the whole panoply of grief that accompanied his passing would have been met with an air of barely concealed contempt by the late Donald Campbell Dewar.

He was a man not given to sentimentality. When presented with a young Leo Blair in Downing Street by a proud father and newly elected Prime Minister, the most he could think to himself was “aren’t all babies really ugly?”.

When friend Kenneth Munro inquired “How’s your mother, Donald?”, he was met with the line “Dead. Quite dead.” Dewar on another occasion dismissed the need for funerals, venturing the view that the council’s cleansing department could save the bereaved money by simply disposing of the body.

These illustrations are not recorded to shock. Rather they are told affectionately, for Donald was, above all, very idiosyncratic, his mannerisms and character traits having their roots in a childhood that was variously strange, unhappy and lent itself to the spawning of an emotionally awkward young man.

He could remain mute or be hilarious, depending on how the mood found him. His manners could be punctilious or he could be spectacularly rude. He could abandon a tract on Gladstone to watch Italian football on Channel 4. His friends adored and were infuriated by him, not quite in equal measure for the core decency of his principles trumped any temptation to bear grudges.

His friends have offered different takes on him. In the only TV documentary ever made on his life (The Dewar Year, STV, 2001), Baroness Meta Ramsay said, as a student, he was sardonic.

The late Donald MacCormick said he modelled his style of debate on Clovis, a P G Wodehouse character who lampooned the vanities of the ruling class. The late Lord Gordon recalled that he could be “odd”. Lord Hattersley told the STV programme that he was intensely private, which was often misunderstood for loneliness.

And yet all spoke of him with a freely volunteered affection which was indicative of a singularly unique personality and one that could be utterly captivating company, when he chose to be.

For a Labour politician from the West of Scotland he was unusual. Born into an upper middle-class family, his parents lived in a grand house overlooking Kelvingrove Park. But they did not keep in the best of health and Dewar was sent to a boarding school in the Scottish Borders before returning to Glasgow, where, somewhat inexplicably, he ended up for a time at Mosspark Primary School.

With his gangly frame, posh accent and staccato delivery he stood out from other children who in turn, bullied him. That, along with parents who were of their time in the affection stakes, produced a young man who was not overly emotional. Any passion came from being moved by ideas rather than people.

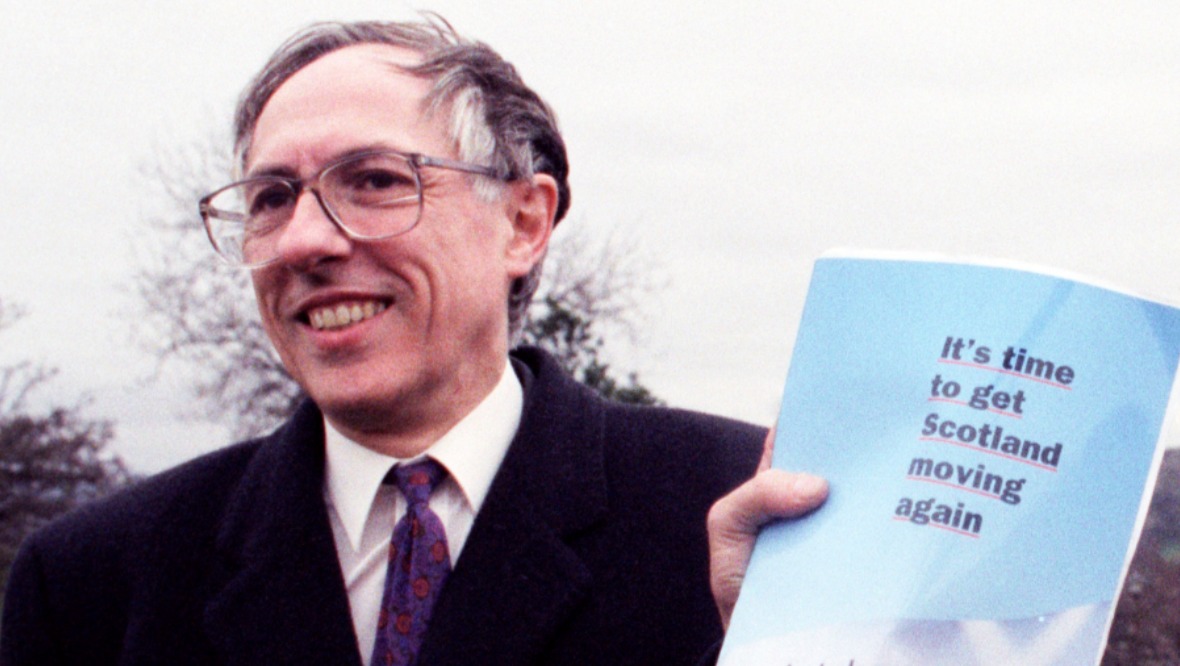

SNS Group

SNS GroupHe came into his own at Glasgow University, where friends included future Labour leader John Smith and Liberal Democrat leader Sir Menzies Campbell. Campbell remembers Donald having the use of his parents’ basement, which provided the venue for student parties.

With an inquiring and logical mind and a natural flair for effortless articulacy, it was perhaps inevitable that he gravitated towards law. But it was politics that was his real passion. Dewar was an admirer of the then-Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell.

Gaitskell was a man who sought to elevate public debate and who took passionate and, at times, emotional stances on great issues. The emotion was fired by the intellectual certainty of his position. In that regard, there was something of the Gaitskell temperament in Dewar for he found passion in causes more readily than he did with individuals.

Gaitskell was a confrontational leader, who, rather than seek peace with those in the party he disagreed with, turned issues into high principle and repeated tests of loyalty. On most issues, the young Donald would have been with Gaitskell as a matter of conviction, although he approved also of Harold Wilson’s more ecumenical style of party management. Wilson succeeded as leader when Gaitskell died unexpectedly in January 1963.

Two years previously, a young John Smith fought a by-election in East Fife. Meta Ramsay recalls Dewar recoiling when he woke up on her shoulder after they headed back to Glasgow by car after a day campaigning for their friend.

SNS Group

SNS GroupBy his own admission, Dewar had little time for girls before university. As he put it in a very Donald way, “we soon put that right”. The attention of his affections was Alison McNair and he would marry her in 1964, just at the conclusion of his studies.

At the general election that year, Dewar was sent north to fight the Conservative-held seat of Aberdeen South. Harold Wilson won across the UK at that election, Labour returning to power after 13 years in opposition. Dewar cut the Conservative majority in the Granite City to under 4000.

Two years later, Wilson called a general election and won a landslide. Back in Aberdeen, Dewar unseated the formidable Priscilla, Lady Tweedsmuir who had been a Scottish Office minister.

In 1967, he was appointed as parliamentary private secretary to Anthony Crosland, then education Secretary and the foremost social democratic thinker in Britain. Crosland’s seminal work, The Future of Socialism, published in 1956 remains the bible for revisionist thinkers on the Left.

An intellectual giant who spoke in a distinct upper class voice, C A R Crosland should have been Dewar’s dream minister. But they did not get on. The Scottish MP found that Crosland “spoke in a sort of intellectual short hand and if you couldn’t keep up then too bad”. Dewar also found Crosland’s lionising working-class MPs who were useless to be annoying.

In the 1966-1970 parliament, Dewar would have been regarded as one to watch. In Scottish Labour circles, the dominant figure was the all-powerful Scottish secretary Willie Ross. For Prime Minister Harold Wilson, Ross and Labour in Scotland were one and the same thing and the man dubbed in party circles as the ‘king of Scotland’ was impressed by Dewar.

Ministerial conferment would have come after the 1970 election but Labour unexpectedly lost. Donald Dewar was unseated by Ian Sproat of ‘dole queue scroungers’ fame. To pile personal misery on top of political calamity, his marriage collapsed when his wife left him for Derry Irvine, a future Lord Chancellor in the Blair government.

He returned to the law, working as a reporter to the Children’s Panel and presented a programme on the new Radio Clyde, founded by his university friend Jimmy Gordon. He sniffed around many nominations and lost them all, including to Dennis Canavan in West Stirlingshire just before the February 1974 general election.

Just as he must have thought a return to Westminster was never going to come, he landed what looked like a pact with political suicide. Dewar was selected to fight a parliamentary by-election in the Glasgow Garscadden constituency in 1978.

The election came at the height of the Labour government’s attempt to legislate for a Scottish Assembly. The party was divided on the issue, both in parliament and the country. To make matters worse, in a portent of what would come 29 years later, the SNP threatened to defeat Labour in their central belt heartland seats.

In what proved the watershed of all watersheds, Dewar held Garscadden and after further victories for Labour at Hamilton and Berwick and East Lothian later in 1978, 70s nationalism endured a profound retreat.

The Garscadden campaign was bitter and ugly. Dewar was pilloried for his pro-abortion views, having to run a gauntlet one evening of young girls in Holy Communion dresses with people whispering ‘murderer’.

The gentlemanly SNP candidate Keith Bovey, a leading light in CND, had to endure bitter attacks too in a seat that neighboured Yarrow Shipbuilders.

The Garscadden legacy was profound as it reasserted the party’s dominance in Scotland and saw off the SNP, who would borrow a leaf from Labour’s book as they went hell for leather in the internecine warfare stakes.

SNS Group

SNS GroupGarscadden was a mile up the road from Donald Dewar’s home in Glasgow’s west end. Behind the grand façade was a threadbare home. Dewar had little time for materialism. Works by the Scottish colourist FCB Cadell were kept in bubble wrap under the stairs.

The home was not centrally heated and outside he drove an old Allegro, the interior of which resembled a battlefield. He joked that someone mistook a Yarrow Shipbuilders tie for one by Yves Saint Laurent, misreading the motif.

If representing Aberdeen South was always an electoral high-wire act given its marginal status, Glasgow Garscadden would be a job for life. It included the sprawling Drumchapel housing scheme alongside the more genteel community of Knightswood.

Dewar was a conscientious MP who abhorred the lack of opportunity for children from poor backgrounds. His life’s work politically was to “right the social arithmetic”, as he put it.

His beliefs were classically social democratic with a value system rooted in equality, social justice and redistribution of wealth. To that should be added values from the Liberal tradition of personal freedom and constitutional change.

Labour lost the 1979 general election and it was the social democratic tradition that Dewar embraced that many in party circles turned on as one that had betrayed the working class and mismanaged capitalism just like the Tories.

The post-1979 civil war saw an upsurge of cult personality politics around Anthony Wedgwood Benn (or Tony as he had become), an embrace of a Marxist analysis and democratic centralist views on making MPs and the party the servants of activists rather than electors.

Dewar was prominent in the Labour Solidarity Campaign aimed at stemming a drift to the unelectable Left. In his constituency he came under heavy pressure and had to see off a challenge to deselect him.

A resident of the Hillhead constituency, he took his mother to vote in the memorable by election of 1982. She voted for ‘that nice Mr Jenkins’ as the former Labour deputy leader defeated the Labour candidate in his new colours as an SDP standard bearer.

Dewar became shadow Scottish secretary in 1984, a recognition of his competence and parliamentary ability. He spoke at lightning speed, the Hansard stenographers frequently left befuddled by his pace and vocabulary. He served his time on the Scottish Affairs Committee, which he chaired for a year in 1980.

For much of the 1980s Donald Dewar was the face of Labour in Scotland. The job would have felt like a long lament for industrial Scotland as he opposed the government on factory closures and the rundown of traditional industries, particularly steel manufacturing and coal mining.

The Proclaimers song, Letter from America, summed it up well; Bathgate no more, Linwood no more, Methil no more, Irvine no more and throw in Lochaber, Sutherland, Lewis and Skye for good measure. There was not a part of Scotland not touched by mass unemployment.

Despite a ‘Scottish Resistance Campaign’ inspired by those on the SNP Left, the nationalists still had not recovered from the post-Garscadden slide and voters looked to Labour and Dewar to remove what they saw as the root cause of joblessness: a Conservative government elected across the UK.

The 1987 general election was fought on the so called ‘doomsday scenario’: Scotland votes in large numbers against the Tories but ends up with a Conservative government on the back of votes elsewhere in the UK.

Dewar was to lead a group of 50 Labour MPs elected in 1987, quickly dubbed the ‘feeble 50’ by the SNP. The 1987 election was a vindication of his measured leadership, but he would have known deep down there would be trouble ahead. Electoral frustration was bound to test voter loyalty.

Margaret Thatcher did nothing to help with the poll tax. Introduced in Scotland before the rest of the UK, it re-energised the SNP, who quickly adopted a non-payment campaign. Dewar’s measured and strictly within the law approach allowed Labour’s detractors to indict on the basis of political impotence.

When Jim Sillars captured Govan for the SNP at a by-election in November 1988, there followed months of soul-searching within the party. Dewar’s response was to hold his nerve and take a calculated gamble.

His gut instinct – which largely proved correct – was that the SNPs non- payment campaign would provide a short-term boost but would not alter electoral fortunes long term, particularly as the consequences of non-payment became clear and helped to spark voter disapproval.

And by committing Labour to embrace a Constitutional Convention on Home Rule, he championed a cross-party approach in deciding the shape of a future Scottish Parliament. This was not done for reason of expediency. Dewar genuinely believed the project on forging an agreement on future governance should be owned by all of Scotland.

His decision to back the Convention was the major strategic decision he took at this time and the consequences were profound. The Convention was to be the bedrock on which the Holyrood parliament was built.

The SNPs decision not to participate also played well for Labour. Seven months after Govan, Labour saw off a challenge in neighbouring Glasgow Central and by the time of a double by-election in Paisley in 1990, the SNP had been put back in their box in shades of 1978.

The man who had stopped 70s nationalism looked to be putting the break on progress for the SNP over a decade later.

But still there was the issue of delivering a parliament and that would only come with a Labour government. There was therefore a sense of feverish excitement as campaigning got underway at the 1992 general election.

Thatcher was gone, but her party remained unpopular in Scotland. John Major looked dull and unimaginative. Unfortunately for Dewar, Neil Kinnock couldn’t seal the deal with voters and Labour went down to a fourth straight election defeat.

He was profoundly depressed. He confided in Helen Liddell that perhaps he was part of a generation that would never be in government. He had held the line against the SNP attacks and from internal critics and he did so with skill and fortitude, for some of the attacks were deeply unpleasant.

His great friend John Smith succeeded Kinnock as Labour leader. Dewar was on the move, becoming shadow social security spokesman. At this time he was probably the most recognisable politician in Scotland and was well respected but he had led for nearly a decade, so time was right for a move.

He was a great details man so the brief appealed. And, of course, the correct policies could help to ‘right the social arithmetic’. He proved masterful in the role.

In May 1994, John Smith died of a heart attack at the age of 55. It was a crushing blow. Dewar gave a typically well-judged tribute at Smith’s funeral. The pain of the loss was etched on his gaunt face, which took on an almost haunted look.

Tony Blair succeeded Smith. He had shared an office with Dewar, whom he referred to as DD, much to Dewar’s studied indifference. In any case DD was on the move again as he became Labour’s chief whip.

The appointment was met with incredulity by some as Dewar is the last person imaginable to be wielding big sticks or strong arming recalcitrant MPs. In retrospect he was an inspired choice. His deputies were the enforcers and he could be left to proffer advice to Blair on parliamentary tactics.

The job also appealed to the gossip in Dewar. He loved gossip principally for the amusement value it gave rather than any bent for prurience or the taking of delight in misfortune. He could pretend not to be interested in some nugget of scandal but hated not knowing.

He could be genuinely bemused by the sexual antics of colleagues or by behaviour he considered odd. Crossing Parliament Square with a journalist friend on the night of a vote to equalise the age of consent, he looked at what he considered a ‘freak show’ of drag acts, men dressed as nuns and assorted Village People wannabees. “How are you voting tonight Donald?” “For 16, of course,” came the definitive reply.

The Conservative government of John Major was killed by ridicule. A speech by Major on ‘back to basics’ was inaccurately interpreted as a crusade for family values. The tabloids crucified MPs whose sexual or financial affairs transgressed what they thought the Prime Minister had implied was morally reprehensible.

No lurid detail was spared from the collective public guffaw. As the Labour MP Brian Wilson remarked, Tory MPs were resigning by the week to spend more time with other people’s families.

As chief whip, Dewar would have been the keeper of the black book of scandal on his colleagues, but he remained tight-lipped on his contents. By that time he would have known that ministerial office was not too far away.

After the Blair landslide in 1997, he became Scottish secretary, a job most thought would have gone to George Robertson. Dewar recalled that Blair said “I am sending you to Scotland”, adding “as if it was a command to go to the salt mines”.

The move was the right one. No-one was better suited to deliver Home Rule and he was temperamentally the right choice in bringing strands of opinion together. George Robertson was always more tribal, particularly when it came to dealing with the SNP.

The White Paper on the devolution legislation was a model of clarity. His leadership was crucial in forging a cross-party consensus which materialised in the form of the ‘Yes Yes’ campaign ahead of a referendum in September 1997.

Dewar was in his element and at the height of his powers. The referendum result saw voters back the idea of a Scottish Parliament with the ability to vary tax. In reality, the anti-Home Rule group Think Twice posed little problem to the Yes forces and Dewar worked well with SNP leader Alex Salmond and with the leader of the Scottish Liberal Democrats, Jim Wallace.

Dewar then published the legislation creating the parliament, telling assembled journalists: “Clause one of the Bill could not be clearer. There shall be a Scottish Parliament. I like that.”

There was some behind-the-scenes friction with other ministers over some of the clauses in the Bill, but Dewar, with skill and persistence, managed to get what he wanted.

The one mistake that was made around this time was to put a price tag on the building of a new parliament, which was estimated to be between £10-40m. This would come back to haunt Dewar, who early on in his ministerial tenure had concluded that the Calton Hill site was unsuitable for the new institution.

A design competition would eventually choose the Catalan architect Enric Miralles to oversee a building which Dewar believed should be a piece of landmark architecture.

The first elections to the Scottish Parliament delivered expected victory for Labour, but the new PR voting system meant that they had to cast around for coalition partners. The negotiations with the Liberal Democrats were not always easy and on a couple of occasions Jim Wallace was ready to walk, but eventually the two parties agreed to form the first government of the devolved era.

July 1, 1999 marked the day when the Scottish Parliament assumed legislative authority. In a masterful address to MSPs, Dewar delivered the speech of his career. He placed the day in a historical context and drew inspiration from great events that shaped the Scotland he was honoured to lead.

At that unique moment there was no-one who could rival him. He looked and sounded the part and stood ready to better the common weal, to start to right the social arithmetic.

His time, however, in government was not a happy one. The scandal of the cost overruns of the Holyrood building project bedevilled the parliament’s early days and he actively considered resigning when he discovered information he had given to parliament was not only hopelessly optimistic but was just plain wrong. It says something about his sense of propriety that trying to spin his way out of a problem never crossed his mind.

As a First Minister he was cautious, perhaps too cautious. His approach was always logical and considered. In his cabinet, ministers jockeyed for the status of ‘most likely successor’. His friend, the late Kenneth Munro, said he did not bring those briefing the media to heel, saying that Dewar suffered from an inability to be a good butcher.

It is true he did not do confrontation and he listened to trusted advisers Wendy Alexander and Lord Murray Elder, although the late Sam Galbraith believed that he should have trusted his own judgements more, arguing that some appointments appeared to be pressed upon him.

Galbraith, a straight talking and frequently blunt man as well as a decorated neurosurgeon, noticed that Dewar’s health was failing. The First Minister sometimes struggled to keep up with Galbraith, which was alarming given that the doctor walked slowly, having had a heart and lung transplant.

Donald Dewar was admitted to hospital for tests on his heart in April 2000 and had surgery a month later to repair a leaking heart valve. This resulted in a period of convalescing at home. He did not, however, rest as he should have and ploughed his way through ministerial boxes. It is now generally accepted that he went back to work too soon.

On October 9, he opened the Glasgow headquarters of SMG, the then-media group that included STV and The Herald newspaper. The following day at Bute House he became unwell. The party’s general secretary in Scotland Lesley Quinn was with him and recalled that the First Minister wore a resigned look similar to that of her mother shortly before she died.

Donald Dewar collapsed at Bute House and was taken to Edinburgh’s Western Infirmary, where he died from a brain haemorrhage. He was only 63.

The sense of shock was profound for he was an admired figure even among those who were not Labour supporters. At his core there was a passion for doing right by parliament, party and people. He cut a reassuring figure and was a world apart from a politics which at the time seemed to be a magnet for spivs and chancers.

Donald Dewar did not live long enough to build and define a new country, but by being the chief architect of a quiet constitutional revolution he became the conductor for all that has gone since his death.

Wendy Alexander has said that he did not have an overarching narrative for a new Scotland, but he knew why he was in politics and whose interests he wished to advance.

Not all colleagues admired him, some noting he could be petty, such as the role he played in blocking a knighthood for Sean Connery despite the actor’s help in campaigning for a Yes vote in the devolution referendum.

The legendary Scottish organiser for the party, the late Jimmy Allison, detected something of the snob in him, an observation those close to Dewar would be quick to dismiss.

Like most men of genuine substance, any weaknesses of character paled into insignificance when set against his strengths.

A final word. I first met him when I was a student. It was in the old North British Hotel in George Square in October 1981. I interviewed him probably hundreds of times. I admired him enormously and was impressed by his values and the integrity with which he pursued them. His death was tragic for his party and the country he felt honoured to serve.

His time in office was relatively short and it was bedevilled with problems. His legacy, however, is huge and it is to be found in the form of Scotland’s Parliament. He is therefore a figure of huge historical interest in the unfolding story of this nation.

SNS Group

SNS Group