By this century’s end, the crumbling, smouldering mass of Manhattan’s twin towers on September 11, 2001, could be the defining image that recast a world that had already moved on from the old cold war certainties.

After 9/11 came the war on terror, war rooted not in empires or conquest or ideology, but by a new fundamentalism apparently rooted in religion.

Its face was irreligious and the consequences defined in unspeakable horror as atrocities multiplied in all corners of the globe.

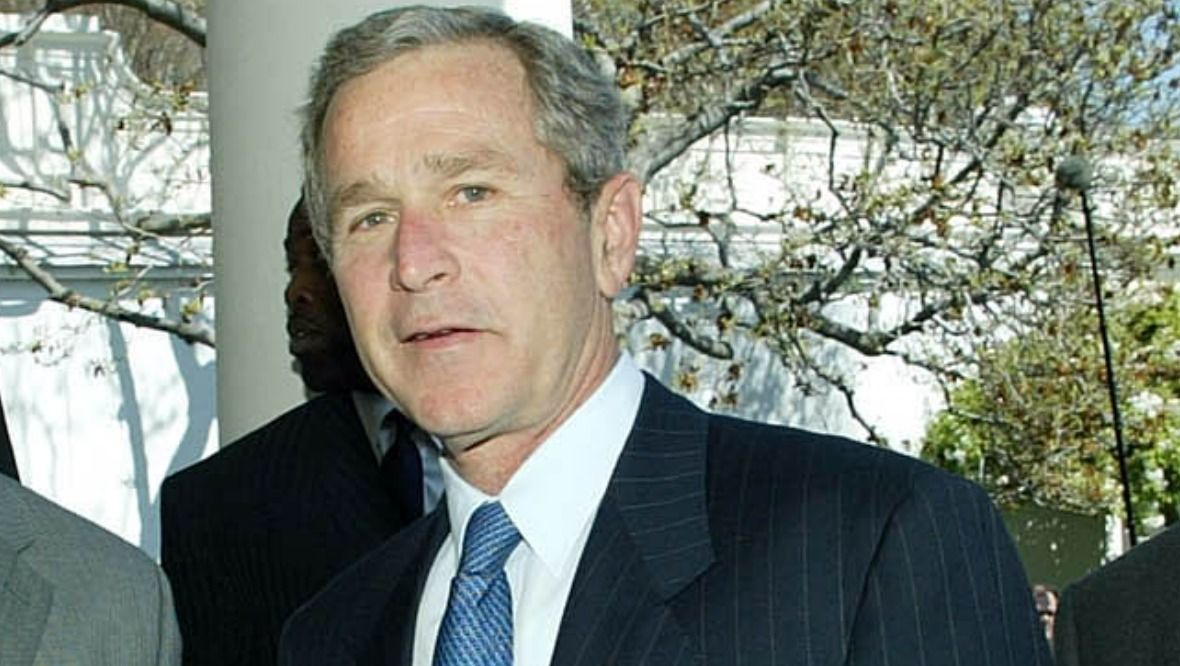

Rarely is a careful, strategic and sustainable response to terror to be found in the raw emotion of witnessing abomination, and yet President George W Bush was driven to respond as quickly as possible.

SNS Group

SNS GroupAmerican intelligence may well have been as certain as certain can be that 9/11 was the work of Al Qaeda and that Osama bin Laden was the orchestrator in chief.

It is, however, stating the blindingly obvious that once the Western coalition decided that it would take the war on terror to the fundamentalists, a military vortex would be unleashed with an endgame that was unpredictable.

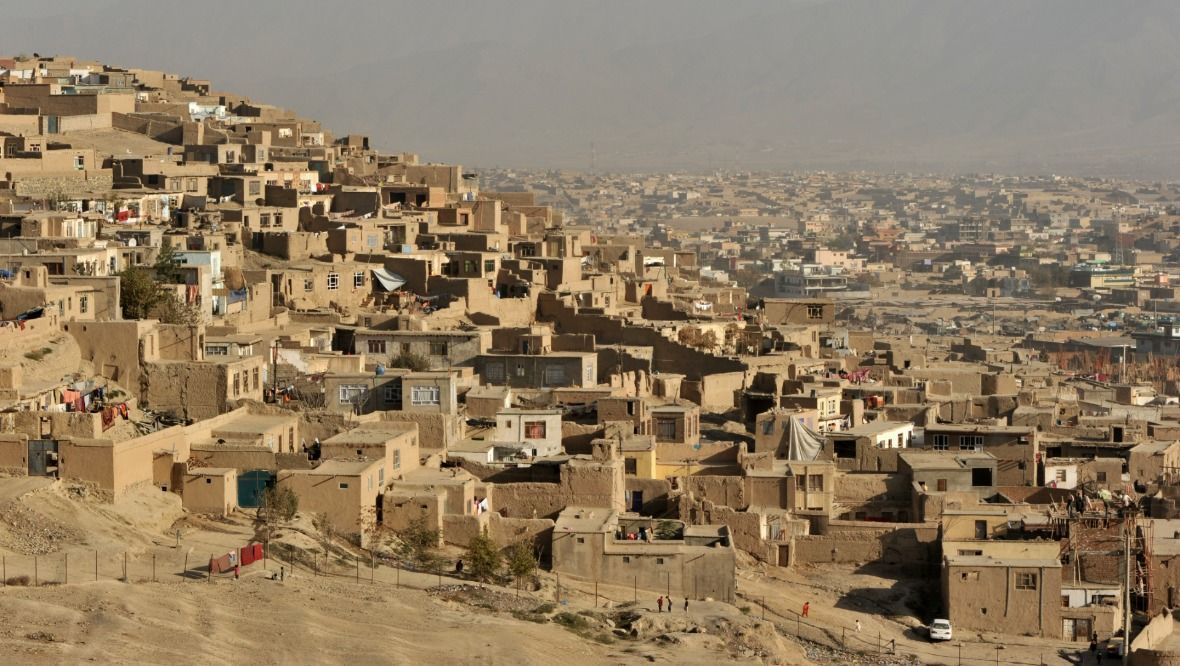

As far as Afghanistan was concerned, the Taliban was removed and a 20-year occupation ended with the defeated as the eventual victors.

Joe Biden may turn his nose up at parallels with Vietnam, but they are only too pertinent. The greatest military might on the planet has withdrawn after spending billions of dollars. The Afghans, like the South Vietnamese, feel abandoned and betrayed. And alongside the anguished cries of those left behind, the question asked by sceptics, ‘what was it all for?’.

Tony Blair’s reputation never survived his evangelising the need to confront the new threat by military means. It started with unconditional support for President Bush and motored through Iraq even when it was less clear what this had to do with the war on terror.

Shifting the terms of engagement, it was weapons of mass destruction that had to be confronted, except they turned out to be elusive.

Many now fear that Afghanistan will return to its old orthodoxy which sees human rights as rooted in deviance. Less predictable is the extent to which new groups will emerge and seek to wreak havoc on the streets of cities around the world.

One lesson that has been learned is that intelligence gathering plays a vital part in countering terror. It is not foolproof, as the bombing of the Manchester arena has only too painfully reminded us, but for many it is preferable to invading countries, massaging regime change and finding out that the law of unintended consequence is the one whose writ runs largest.

iStock

iStockIn the post-war period, electorates, particularly in the USA and UK, had a tendency to back their governments when it came to the deployment of troops at different times and in different conflicts.

There is now a scepticism about this as voters cannot make the connection between what happens in far-off lands subsequently threatening the security of their way of life at home.

In the ‘war versus intelligence’ strategies, it is the latter which will triumph, if only because the twin-track approach of exploiting both incurs the wrath of voters and can be torpedoed by the volatility that electoral cycles bring to long-term policy.

‘Watching in stunned silence’

I remember what I was doing the day the towers fell. I watched with colleagues in stunned silence. Even then as it was difficult to compute, it was clear that the world would not be the same again. And so it proved.

The mood of horror was summed up by Aaron Brown, who drew on his characteristics of calm and quiet authority in anchoring CNN’s coverage that day. He turned as the second tower fell and uttered the line: “Oh my goodness. There are no words.”

The day the towers fell, an old order died. Those who grieved still do. Long after that thick fog of dust and debris stopped engulfing lower Manhattan, a new, crueller and more anguished world emerged from the embers in a battle without resolution and apparent end.