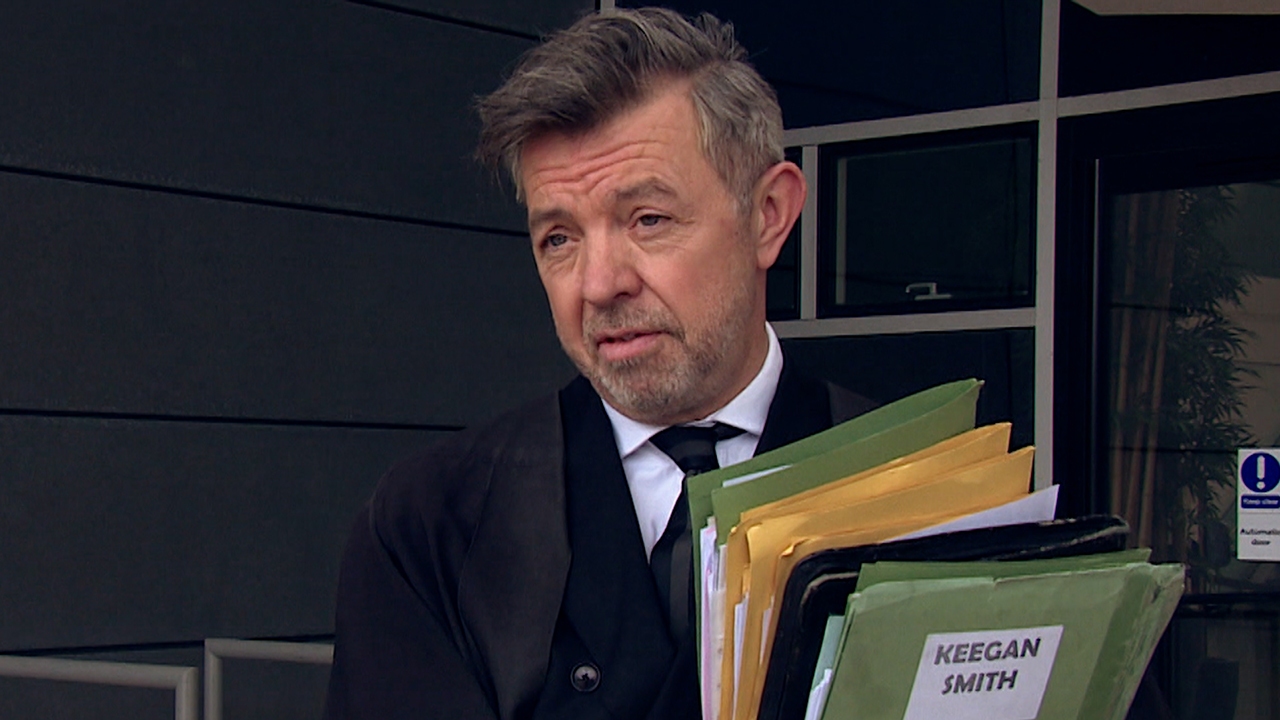

It is just after 9am when defence lawyer Darryl Lovie arrives at Livingston Sheriff Court with a packed schedule.

40,000 trials are waiting to be heard in Scotland, a backlog the court service estimates will take up to four years to clear, and on this typical day, Mr Lovie has four (involving a total of 17 witnesses), a deferred sentence following an earlier guilty plea, and a bail review. These will be heard in three separate court rooms.

By the time we reach midday, Mr Lovie’s court business has concluded. The only case he’s been able to deal with is the deferred sentence, in which the accused was given a community payback order.

His trials have been adjourned administratively without any notice being given to him.

“It would seem that the court had selected three priority trials which were expected to run, none of which were mine,” he says.

“I’ve just discovered that none of those trials have proceeded, all have been adjourned as a consequence of either witnesses or accused suffering from Covid.

“There’s a courtroom sitting empty there for the rest of the day, I have all of these clients who are now going to have to wait until April, May, June for their cases to recur.”

‘Radical action needed’

In the afternoon, Mr Lovie heads back to his office at Keegan Smith to work through paperwork and deliver the news to clients that their cases have been pushed back another day.

“No-one can tell me for a moment that a practical solution couldn’t have resulted in business being dealt with throughout the course of an entire day at Livingston Sheriff Court today,” he says.

“Today’s experience is being replicated in courtroom after courtroom, in court after court, in town after town, in city after city, across the country – on a daily basis.”

As the representative for the accused in criminal cases, Mr Lovie has concerns about the impact on everyone involved.

“It will often be the first thing they think of in the morning, and the last thing they think of before they go to sleep,” he says.

“We all know, unfortunately, that the build up of tensions and frustrations, for instance within a family home, can lead to loss of temper and further offending.

“The criminal justice system was failing pre-Covid, and from the defence profession’s perspective, we were in freefall, terminal decline. All Covid has done is accelerated that decline.

“If you’re stretched to breaking point, as we have been for some time, then you can’t produce your A-game. It’s as simple as that. And that’s when access to justice suffers. The reality is this backlog, as things currently stand, will never be overcome.

STV News

STV News“Radical action is needed, immediate action is needed – we are not overstating the position when we say this is a full-blown crisis. Solutions need to be sought to try and get cases off the books, it’s as simple as that.”

He also raises concerns about the lack of equality between the Crown and the defence side of the table.

“There are bigger arguments in terms of the system as a whole, whether it’s fit for purpose,” he says. “In order that fairness can be achieved, then, in an adversarial system where the Crown is pitted against the defence, there needs to be an equality of arms, and there simply isn’t.

“The shadow produced by the backlog is getting longer.”

‘Determined to catch up’

Justice secretary Keith Brown told Scotland Tonight he was “determined to get through the backlog”.

He said: “We’ve already introduced additional new monies, over £50m this year – the same again for last year as we have this year. Not only that, we’ve had 60 new courts brought in to try and process some of the backlog.

“We had some really important innovations like remote jury centres and so on. We’ve got additional courts… but we have a finite number of people and resources in the system.”

Speaking after launching the Scottish Government’s new Vision for Justice, which outlines a number of measures to improve the system, Brown said there were “better solutions” than simply putting more people in prison.

The plan also says victims will be put at the heart of the process, and offered more support.

Brown added: “This strategic blueprint sets out key priority areas, including improving the experience of women and girls in a justice system historically designed by men, taking forward reform to address inequalities.

“It also stresses the need for a fresh look at the use of custody and firmly puts victims and the needs of victims at its centre.

“Underpinning this, the vision makes clear the need for services to be person centred and trauma informed to avoid re-traumatising people as they journey through the system.”

Eric McQueen, chief executive of the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (SCTS), said court staff had worked quickly to adapt over the past two years.

He championed innovations such as remote jury centres – in which juries are based in cinemas – and virtual custody hearings. And he said work was underway to continue the “recovery” from lockdown.

He added: “One interesting thing we’re working on is about domestic abuse, which accounts for 25 per cent of the cases in our court.

“We’re trying to do that in a virtual environment, where we don’t actually bring people into the courtroom, but [put] proper trauma informed practices in place… and provide a better environment.”

Before the pandemic, it would have taken an average of six months between a High Court case first calling and a trial starting; currently it’s taking around a year. In the sheriff court, it would normally take around four months, now it’s more like ten months.

Mr McQueen estimates that the courts can catch up to pre-Covid levels by March 2024 for summary (sheriff) cases, and March 2026 for High Court business.

He added: “Yes, the backlogs are a big issue, but we are taking every step we can to try to minimise the delay to these for the obvious reasons – the impact of people involved.”